Balfron Listing

In August 2014, I worked with James Dunnett of DOCOMOMO to write a listing upgrade nomination for all of Ernö Goldfinger's buildings and spaces at the Brownfield Estate. In October 2015 Historic England and the Department for Culture, Media and Sport accepted our bid and upgraded Balfron's listing to Grade II* and Glenkerry House to Grade II.

The decision is important for our ongoing campaign to save Balfron’s social housing as this Grade II* listing formally recognises the social ideals and purpose of the tower as a key component of its heritage.

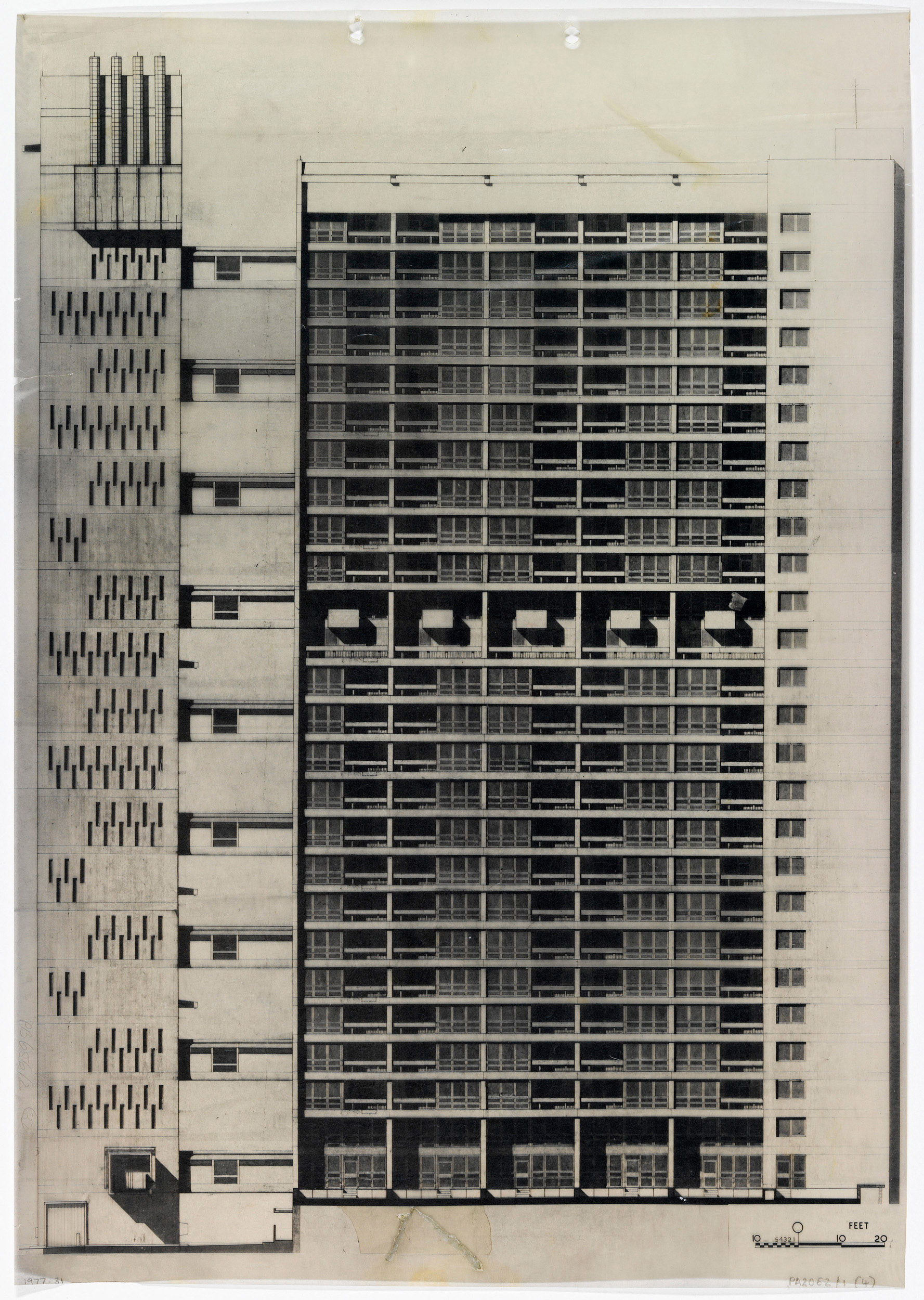

Historic England state: "Balfron Tower was designed as a social entity to re-house a community, according with Goldfinger's socialist thinking.” And among their ‘principal reasons' for listing, they note: “Architectural interest: a manifestation of the architect’s rigorous approach to design and of his socialist architectural principles” and "Social and historic interest: designed to re-house a local community”.

Privatising Balfron will destroy these principles and this heritage. Saving Balfron’s social housing will keep these principles and this heritage alive.

Our reasons for the nomination include:

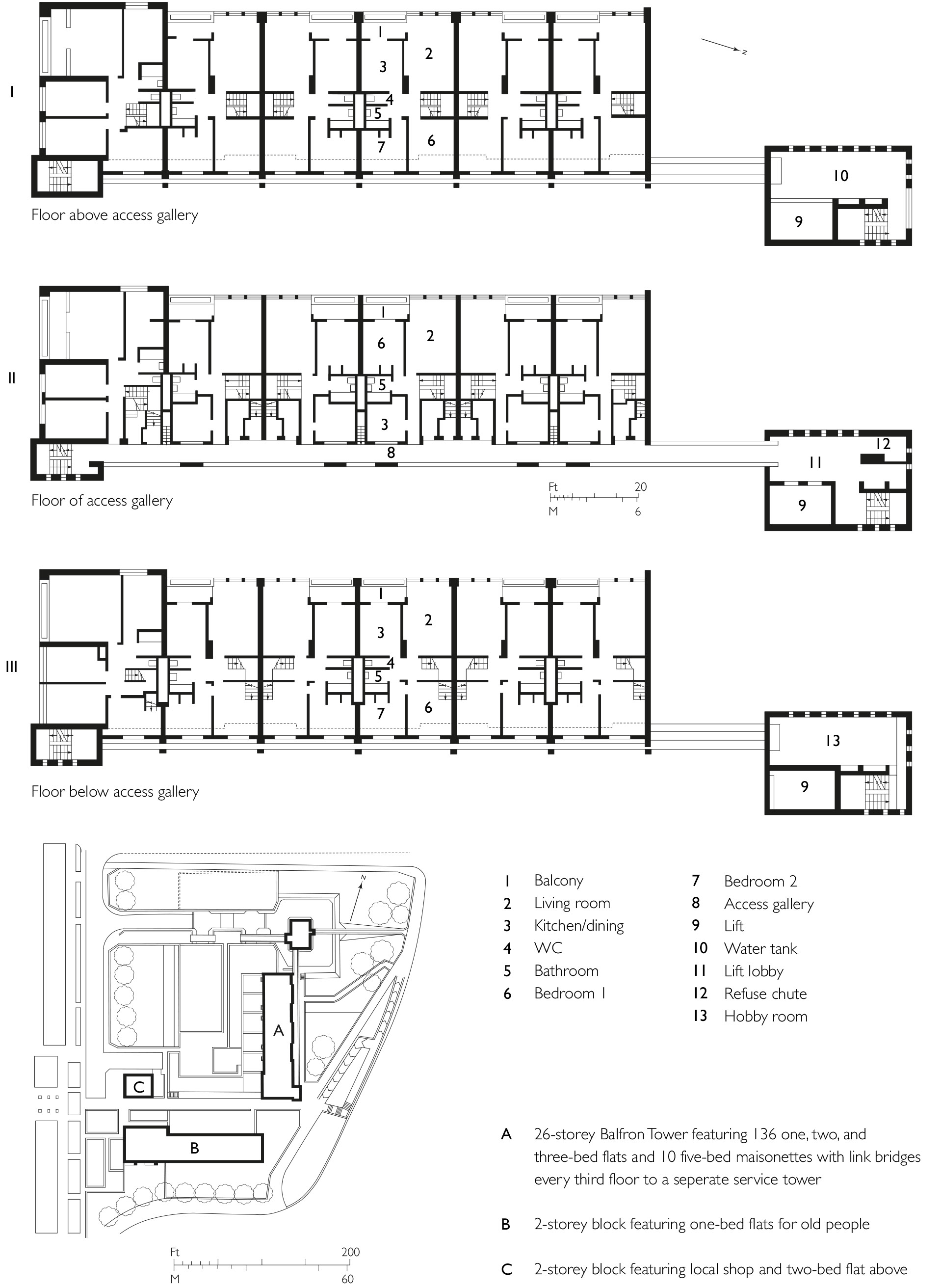

- Goldfinger’s buildings and spaces on the Brownfield Estate are already protected by the Conservation Area, but only Balfron Tower and Carradale House are listed. All of these should be listed at the same level of listing as Trellick Tower in North Kensington, including specifically the spaces between the buildings which can be vulnerable to development pressures, to recognise the exceptional architectural qualities of Goldfinger's work on the estate.

- A Grade II* level of listing would ensure that Historic England was actively involved in assessing any application for listed building consent for alterations or additions of any kind (which otherwise would be at the discretion of the local authority) and could make additional funding available via Historic England and might perhaps make it more possible for DCMS to help funding for refurbishment within the social housing sector.

- The current listing descriptions of Balfron Tower and Carradale House are inadequate and should be elaborated on to include all their ancillary buildings, reflect the social elements in the design and preserve the social purpose of this housing.

In support of this final point I produced a supplementary document devoted to residents’ experiences, drawing from residents’ own words to identify the aspects of the building they cherish and convey how unique design features have framed their everyday experiences.

I had been inspired by the rallying cry of Emma Dent Coad, an architectural writer and local councillor who represents the residents of the Cheltenham Estate comprising Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower and once chained herself to a care home on the estate to protest its imminent demolition by the Council. In her article on preserving buildings such as Trellick within the social sector, she implored academics to act proactively ‘we must get our hands dirty to engage politically, comprehensively and at the right time… If we determine that social purpose must also be conserved, we must look beyond physical conservation and commit to keeping these homes in the social sector.’ At the same time, the potential of this notion of conservation was being demonstrated by campaigners fighting against the conversion of Berthold Lubetkin’s Finsbury Health Centre who had built their case on the fact that its original use as a community health clinic was written in the listing description.

In his supporting statement to the listing, Owen Hatherley concluded:

‘The listing of buildings should always be careful not to be just a matter of listing a few lone ‘icons’ to be preserved as toys, and be careful not to list buildings as shells that can be filled with anything, particularly when their purpose is still very much needed. On this basis I support the listing of the Brownfield Estate as a whole as a coherent, well made and complete example of public housing well above the current standard of private housing - and which must stay as public housing, in an area that desperately needs it. On both architectural and social grounds, this is a place which needs preserving.’

Excerpt of Residents’ Experience Document

[Domestic experience] Common to residents is a feeling of intimidation upon first seeing Balfron, a building many would have never imagined inhabiting. This evokes negative associations, the ‘kind of thing that you think of with inner-city tower blocks, but actually I found it to be a very different experience when I moved in’. ‘When I knew I had to live here and I didn’t have any choice, I wanted to run away, I didn’t know anything about the tower. As soon as I moved in to the 21st floor I just total fell in love with it, everything about it’. Whilst its architecture is still too brutal in expression to some eyes, there is universal appreciation of the private and sociable ways of life it accommodates from within, ‘It’s a very trendy thing now, it’s in fashion – what I like about it is being inside it’.

[Interior layouts] Residents value the organisation and character of interior layouts, ‘It’s a lovely size in terms of the flat and I love the design’. ‘I think the flats are wonderful places to live’. ‘I can’t think of anything I’d change in this flat.’ The flats delighted first tenants as they were bigger and lighter than anything they were used to, ‘it was like a palace’, and are still recognised as superior today, ‘The flats are a great size, spacious - a luxury considering all the shoe boxes being built’, ‘It’s a better design than anything now’, offering ‘the space to reflect and create’, ‘to live in I don’t think you can get much better’.

[Materials and detailing] Over decades of changing fashions, the interiors have been decorated to different tastes - overlaid brick cladding, thick pile carpets, patterned wallpaper - but many of the original design features remain and have lasted well, such as the full height timber windows, light switches set into door frames and pre-cast flower boxes that have encouraged wildlife - herons, peregrine falcons and ‘squirrels [that] made it regularly to what I assume was the twenty-third floor’. ‘The planters are very useful. I don’t think we would have thought about growing anything if they hadn’t been there. They also have a self-draining mechanism which makes it easy to water them. Since living here my flatmate and I have really got into tomato and marigold growing’. Residents admire the ‘tremendous force attached to its material and its detailing’ and the privacy that comes from ‘very good soundproofing’ and ‘low noise from neighbouring flats’ which enable some to feel ‘enclosed and safe’. A mother described how it was a nice environment to raise her baby in Balfron ‘because the flats were quiet’ and ‘really well designed’.

[Quality of light and views] Most flats are double aspect except those on the south-face that are triple and two-person flats that feature a sash window in the kitchen which opens onto the walkway facing east. Though residents complain that the full height partially glazed screens can be draughty, they cherish the quantity and quality of light they provide. ‘Goldfinger designed with an awful lot of light. You live in the space in a different way. It affects your being. And that’s critical to your entire existence’. ‘I felt an incredible calm and feeling of wellbeing’.

No matter how high residents live, with different proportions of city and sky, the view has become vital to a sense of spaciousness and belonging. It enhances the space in flats, giving the feeling ‘like you have an outdoor space in your front room’, that ‘extend[s] outside the boundaries of our living room’, but also of the estate, ‘The view, not just outwards towards London skyline but inwards towards the Brownfield area. It’s a very communal view and often there are kids playing in the sunken playground. It’s been lovely these past few weeks of summer to come home and have a cup of the tea on the balcony and just listen to the sound of activity below’.

The view is a source of personal contemplation and identity; ‘The fact that it’s in the sky is so important to it. I do feel a Londoner up here, ironically, you do see the cranes, you see the horizon as it changes, to see the Gherkin being built, to see the Shard, incredible’. ‘Especially at the night coz everything was lit up… To me it was just like fairy lights. It was like fairy land, truly’. One resident who has lived with view for twenty years fetched a small postcard print of German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog during our interview, ‘That’s me looking out of the window, that’s how I feel looking out of the window. That’s my image of my life in the flat overlooking London’.

The view is also a backdrop and focus to the conduct of communal relationships, ‘You don’t really watch TV when you live somewhere with a nice view... every time you look out you can see different things’. ‘We felt very magnificent being up there. The view, we could see Battersea Power station on a good day, you see everything from there. I think for social housing tenants to lose the view is such a terrible theft of experience’.

[Communal experience] The first to move in remember the sociability concomitant with existing communal ties, ‘I was here forty-odd years. I loved it. Everyone would help one another. You knew your next-door neighbour, you knew everyone. Even in the block, because as we moved the whole street moved into the block with us. So we still knew everyone and there was such a friendship and everything’. When asked about the communal experience today, residents acknowledge the consequences of long periods of poor social policy and unfailingly mention the now sealed-off laundry and amenity rooms, unreliable lifts and inaccessible garages. But the feeling of neighbourliness is not restricted to Balfron’s early ‘golden age’, the nine distinct corridors which lead to three levels of flats offer ‘more chance of meeting neighbours’ and can be a ‘great place to meet the neighbours and chat’. The intimacy these spaces provide is unexpected, ‘it is the first time in my life I’ve got to know my neighbours’, the ‘friendliness isn’t something I’ve experienced in other parts of London’.

[Collective memory] The longest-serving residents remember meeting Goldfinger at his parties, ‘He introduced himself and he asked our opinion of different things, what we thought of this and that. And he weighed it all in, so that when he built the other building, he done the adjustments, you know what I mean’. Similar anecdotes have survived generations of new residents through continued conversations between neighbours, that have meant residents are well informed and inspired by its history. This enduring shared legacy gives a uniqueness to everyday lived experience and continues to bring residents together who learn more about Balfron’s unique architecture and history and consequently feel pride in living here, ‘Trellick is more famous, but this place is more close to his heart in the fact that he lived here’. ‘I tapped into the Goldfinger thing, I painted my whole flat gold… I felt I could be really creative here... [it] opened up a new world to me’.The view is a source of personal contemplation and identity; ‘The fact that it’s in the sky is so important to it. I do feel a Londoner up here, ironically, you do see the cranes, you see the horizon as it changes, to see the Gherkin being built, to see the Shard, incredible’. ‘Especially at the night coz everything was lit up… To me it was just like fairy lights. It was like fairy land, truly’. One resident who has lived with view for twenty years fetched a small postcard print of German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog during our interview, ‘That’s me looking out of the window, that’s how I feel looking out of the window. That’s my image of my life in the flat overlooking London’.

References

Published as Roberts, D. ‘“We felt magnificent being up there”: Ernö Goldfinger's Balfron Tower and the campaign to keep it public’, in Guillery, P. and Kroll, D. (eds.) Mobilising Housing Histories: Learning from London’s Past, London: RIBA Publishing, pp. 141-162.

For more information visit here.