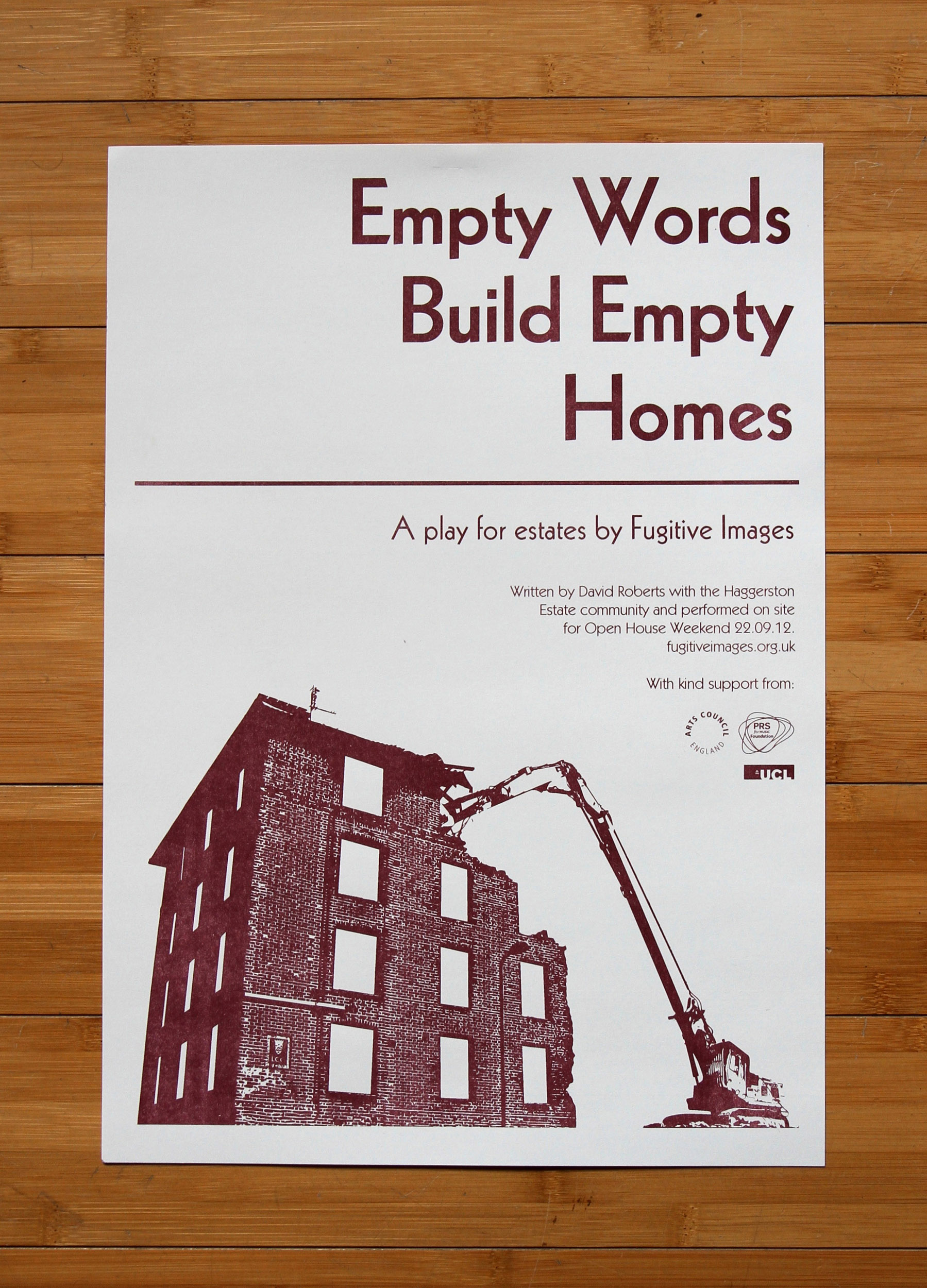

Empty Words Build Empty Homes

Excerpt from Prologue

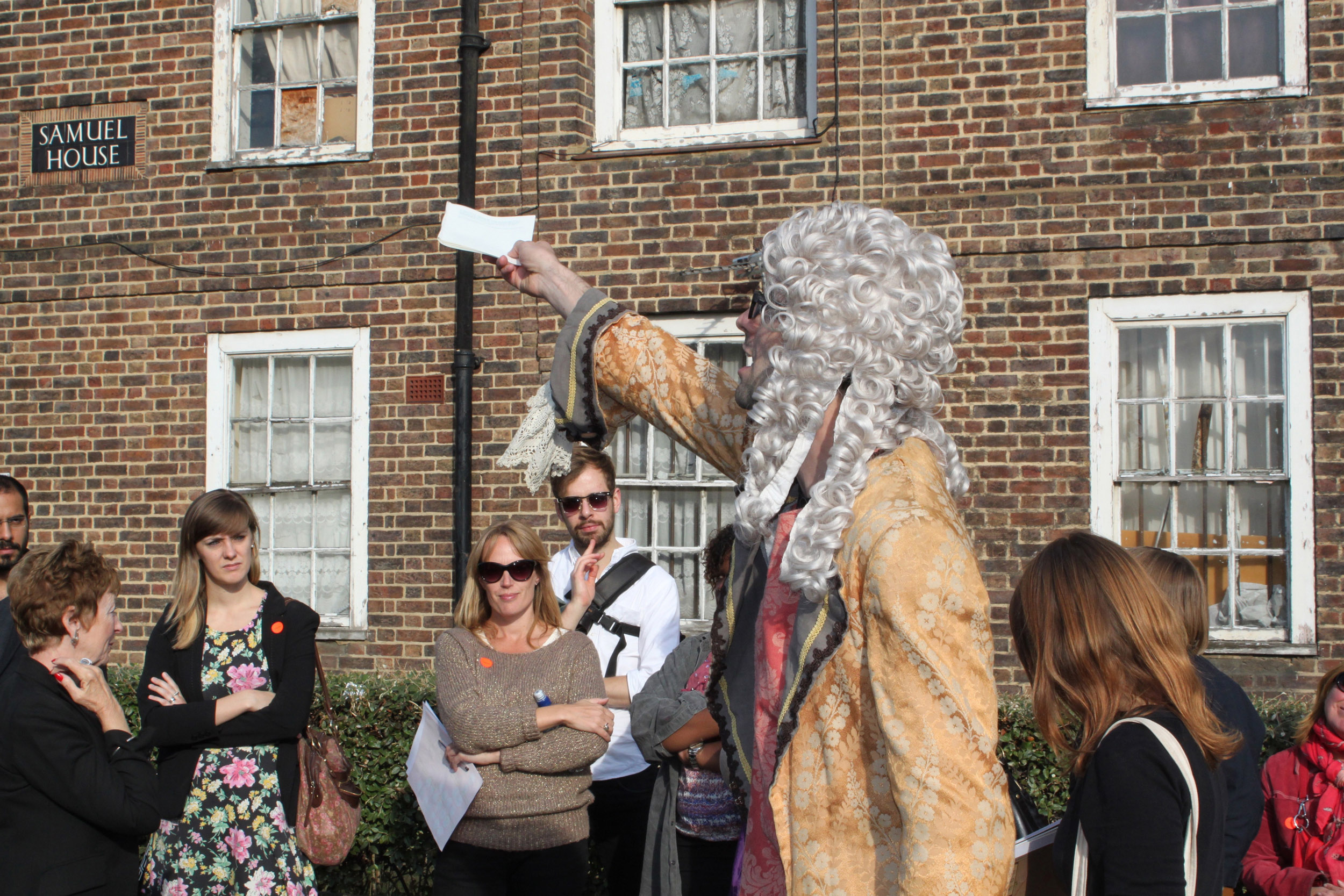

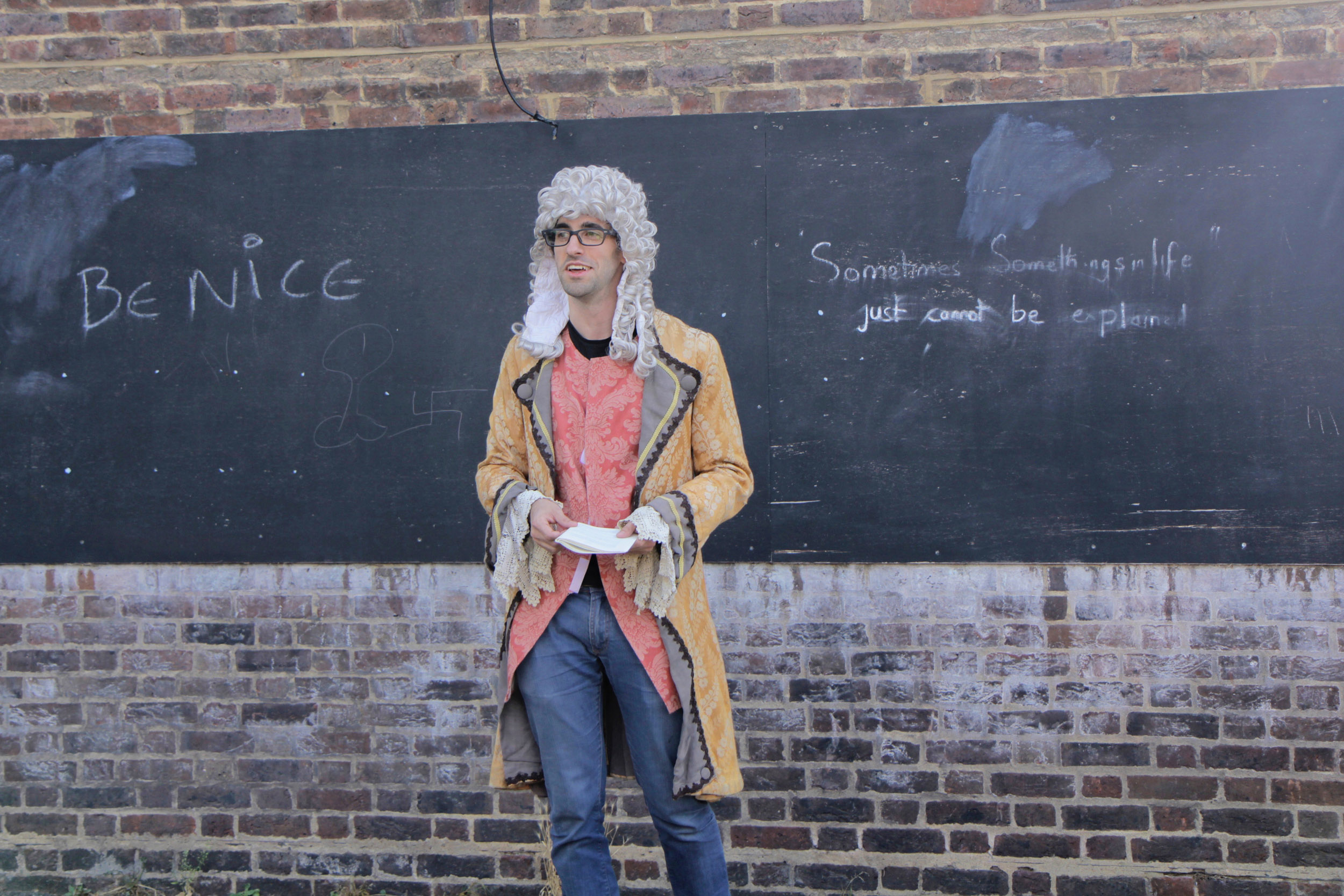

[The story takes place half a decade after the latest economic meltdown (in this case, 2012). The stage a housing estate somewhere deep in the inner city (in this case, the Haggerston Estate in Hackney). One block as ESTATE, one actor as GUIDE, one as NARRATOR, twenty as tour GROUP. The GROUP assembles in the south-east corner of the estate’s inner courtyard. They stand on unmarked tarmac which continues up to the edge of a low wall that runs in front of the gated doors of ground floor flats. The AUDIENCE is scattered across the rest of the courtyard and along the four rows of long curved balconies that form the two-sided five-storey block. The play unfolds while they peruse newspapers on patios, hang clothes from balcony ceilings, play ping pong by picnic tables, water pansies in hanging baskets, share lewd jokes by open gates, steal kisses in the stairwells, cycle feverishly on the grass patch protected by stabilizers. Some catch glimpses of small talk from the gathering GROUP, others spy the NARRATOR and GUIDE descend from a top floor flat. Only the GUIDE reaches the ground, a bespectacled man in a black t-shirt, dirty plimsolls and dark jeans. He hauls a tired leather suitcase to the tarmac before the GROUP, steps onto it and clears his throat. A hush descends. Before he speaks the NARRATOR appears from the first floor balcony above looking past GROUP and GUIDE to address the scattered AUDIENCE].

The NARRATOR [To the AUDIENCE]:

Excuse me please my neighbours, with your grace

I shall explain our presence in this place,

a short interval interrupts your day

while players do a tragic tale convey.

Your Haggerston still stands but only just –

soon balcony and promise turn to dust.

Our characters: this tour group huddled here

drawn by their curiosity and hope to peer

in through your windows to this building’s past;

a guide who’ll challenge prejudice and cast

himself as planner, politician, hack,

as writer, jogger, architect and back

to blame his kind for gentrifying spaces

which still belong to others, (see your faces

in the bricked up windows of this block)

so listen to him and forbear to mock

his heavy glasses, skinny turned-up jeans

perhaps he sounds pretentious, but he means

to show them everything you stand to lose

when we forget your homes behind the news

He’ll take them on a journey – not through time

but through the eyes of others, peel back the grime

of preconceived ideas and try to look

in social housing’s quickly closing book.

So please be patient and save your debate

till he has introduced this great Estate.

Empty Words Build Empty Homes is a site-specific play performed at the soon-to-be demolished Haggerston West Estate in September 2012 developed during a practice-led PhD in Architectural Design under the supervision of Jane Rendell and Ben Campkin. For Open House weekend, I gave two performances of this site-specific play as part of a free day of tours, collective discussions and film screenings I organised for the local community and open to the public.

Dividing my time between residents and research material, I had come to appreciate the disjuncture between lived reality and representation. I felt that Haggerston’s residents shared a history of resistance and resilience but their voices could still not be heard above the cacophony of journalistic clichés that informed public perspectives, correlating material deterioration of estates with social deterioration of their communities.

The Haggerston Estate was used as a stop on what residents described as ‘poverty tours’ where housing associations and charities would showcase the condition of forthcoming sites for regeneration. The play appropriated this medium, offering an alternative tour of the estate seen and understood in the company of its residents, sharing a more informed and complex history, opening up the building and its history of resistance and resilience to others.

The conception, devising and staging of the play draws upon the performative writings of Jane Rendell and Peggy Phelan; the choreography of Mike Pearson’s site-specific performances; and the scenario and scenography of Bertolt Brecht. The script wears these influences openly. With the estate’s imminent demolition, the elaborate stage directions write the disappearance of both performance and building and act as a written record of the estate. They address director, actor and reader, detailing the stage scenery, prescribing actions and imagining a restaging of the estate itself.

Usually tours demand the positioning of an eager guide between viewer and architecture. This performance neither privileges one way of seeing nor allows the audience to rush to conclusions. The performance made public archival and anecdotal, political and personal, bureaucratic and emotional material, casting the tour guide as different figures who shaped the estate – a Victorian surveyor, journalist, jogger, politician, architect, sociologist and resident. As in Rendell’s praxis of site-writing, I wished to make tangible the changing positions we occupy in relation to the estate in our sites of writing. So rather than addressing the history of the estate in chronological order, it is organised according to viewpoint. It begins from the perspective of the most distanced observer and finishes with the most intimate user. This is mirrored in the mode of narration across the three acts; written from third to second to first person; and in the physical location of the tour group, moving around the public outer edge of the estate, into the open courtyard and onto the semi-private balcony.

During the performance I choreographed unscripted encounters with residents to interrupt the seventy visitors expecting a traditional architectural tour with moments of creative participation. I wanted to neither privilege residents nor visitors as the official audience; so the roles of observer and actor differ when the script is performed and read. When enacted on site, it was performed to the visiting tour group as audience. When read, the movements of both tour guide and tour group are directed and controlled through stage directions, with residents as the audience. This had the aim of opening up the site and debate to a wider audience while also revealing representations of the estate back to its inhabitants. To document the performance and these unscripted moments, I asked two residents to photograph and film the event to question whether visitors to the estate were witnessing a community holding its own telling, or whether the residents were still spectators in a story being told by an outsider.

I chose to make explicit the ‘representational apparatus’ – the stage directions, set, costumes – during the performance by incorporating them into the dialogue. The purpose of this Brechtian move was to foreground the audience’s encounter not with my performance but with the building. I continued to be driven by a conviction that choreographing immediacy with blocks like Samuel House, assumed to have failed architecturally and socially, has value experientially and epistemologically in challenging these enduring public perceptions.

The play takes the estate as storyteller, drawing on its dimensions and configuration to determine movement and narrative. It begins with a eulogy to public housing, a rubbish chute as pulpit, and ends with a rallying cry, a balcony as rostrum from which to proclaim the continued and urgent need for public housing as these communities and the qualities they bring to London are diluted or displaced by processes of regeneration.

Excerpt from Epilogue

GUIDE [To the GROUP]:

Trace this cavity in the grout, [running his index finger along the ridge between breeze blocks] can you feel the moment between departure and nostalgia? Measure yourself against it, [standing arms outstretched with back against the bricked up door of a house] can you sense the distance between neighbours? Caress concrete, [sweeping his hand across the floor] does it feel daunting? Lick brick, [rolling his tongue over a painted brick] does it taste rotten? Hug ironwork, [wrapping himself around an iron gutter pipe] does it seem antiquated? Press ears against the tile, [squashing his ear to the balcony wall] can you hear its lost ideals groan? Sniff sash [pressing nose to glass] does it smell hopeless? Jump up and down, [launching himself off the floor] can you feel it sink?

References

Published as Roberts, D. (2014) ‘Telling Stories / Empty Words Build Empty Homes’, Opticon1826, v. 17, n. 16.