Practising Ethics Guides

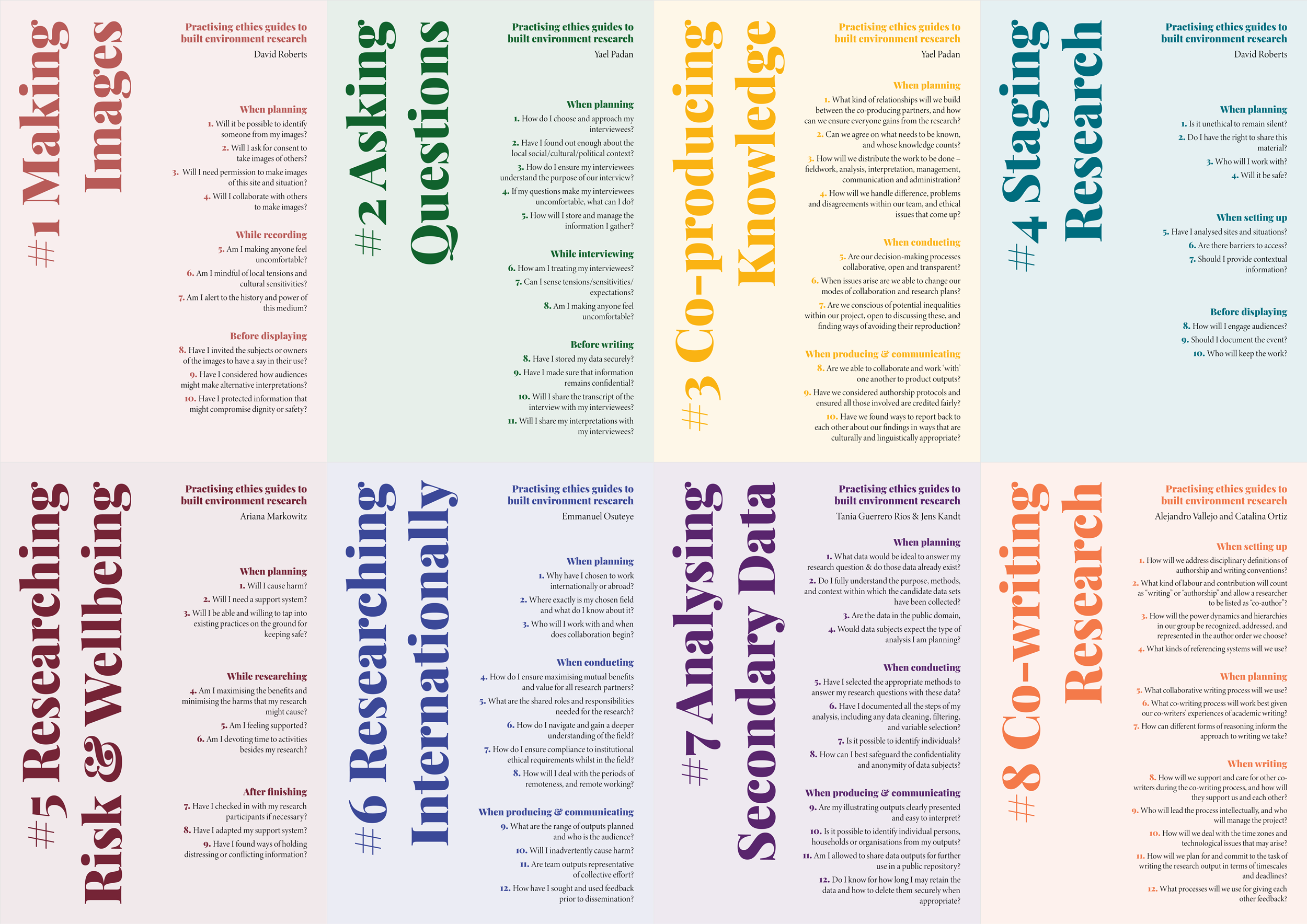

Practising Ethics Guides are part of an open-access educational tool for emerging and established built environment practitioners to teach themselves and others how to identify ethical dilemmas that may arise in research and practice, negotiate their ethical responsibilities, and rehearse strategies to navigate unpredictable ethical issues with care and creativity.

The guides are the result of an interdisciplinary collaboration between two long-term projects - the Bartlett Ethics Commission (2015-2022) and Knowledge in Action for Urban Equality (2018-2022) - that explore ethical protocols for built environment practitioners and strengthen pathways to urban equality, paying particular attention to the western-centric bias of ethical values which privilege the individual over the communal or collective. Together, this research explores the relationship between universals and specifics through a framework that encourages a situated mode of ethical practice, which situates the relation between universal principles and particular processes in specific contexts. The guides help navigate this relationship by using generative questions as prompts for practitioners to reflect on potential ethical considerations and by setting out guidelines that contextualise concerns and suggest potential actions.

Practising Ethics Guides are designed as an accessible point of reference at all stages of a project — from planning research and conducting activities in the field, to producing and communicating outputs. Rather than a regulatory hurdle, they consider ethics as an opportunity to enrich architectural practice through reflexive curiosity and critical investigation.

Two questions sit at the heart of our project: ‘What is an ethical practice of built environment research?’ and ‘How do we foster the conditions for emerging and established practitioners to develop this?’ By defining ethics as a situated but also a relational practice, it is possible to see that developing an ethical research practice involves responsibility, reflection, and recognition. But how to help researchers develop ethical attitudes and aptitudes that cultivate acts of responsibility, reflection, and recognition? A desire to achieve a balance between the reflective and the active has been a fundamental aim of our approach, and for this reason our guides focus on the use of questioning to generate reflection and on the act of guiding itself to encourage the taking of responsibility and recognition of the other.

Addressing the lives and stories of Others, D. Soyini Madison reminds us, is always ‘a complicated and contentious undertaking’. To illustrate what is at stake, she invites researchers committed to addressing processes of unfairness and injustice to consider five central questions:

i. How do we reflect upon and evaluate our own purpose, intentions, and frames of analysis as researchers?

ii. How do we predict consequences or evaluate our own potential to do harm?

iii. How do we create and maintain a dialogue of collaboration in our research projects between ourselves and Others?

iv. How is the specificity of the local story relevant to the broader meanings and operations of the human condition?

v. How — in what location or through what intervention — will our work make the greatest contribution to equity, freedom, and justice?

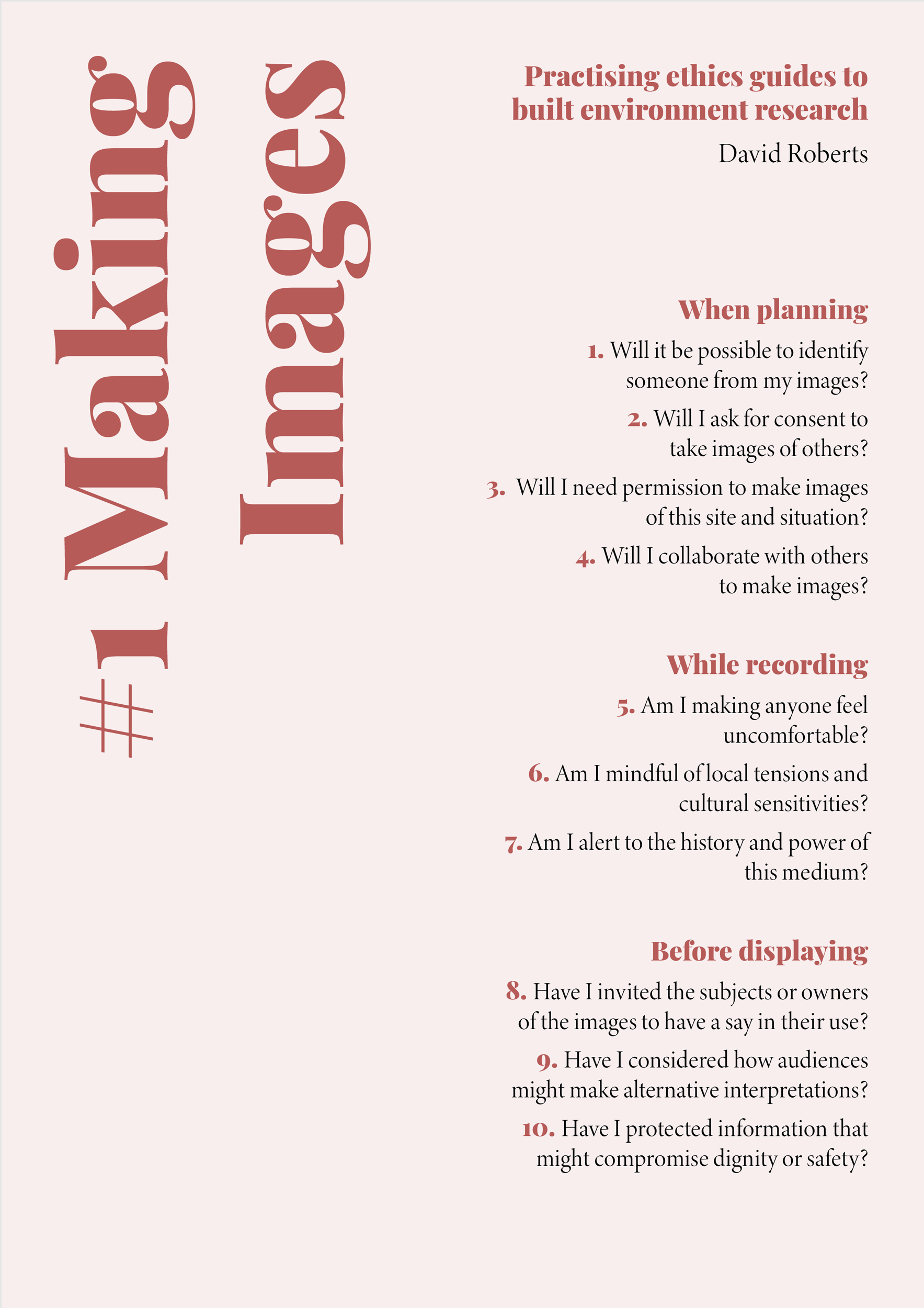

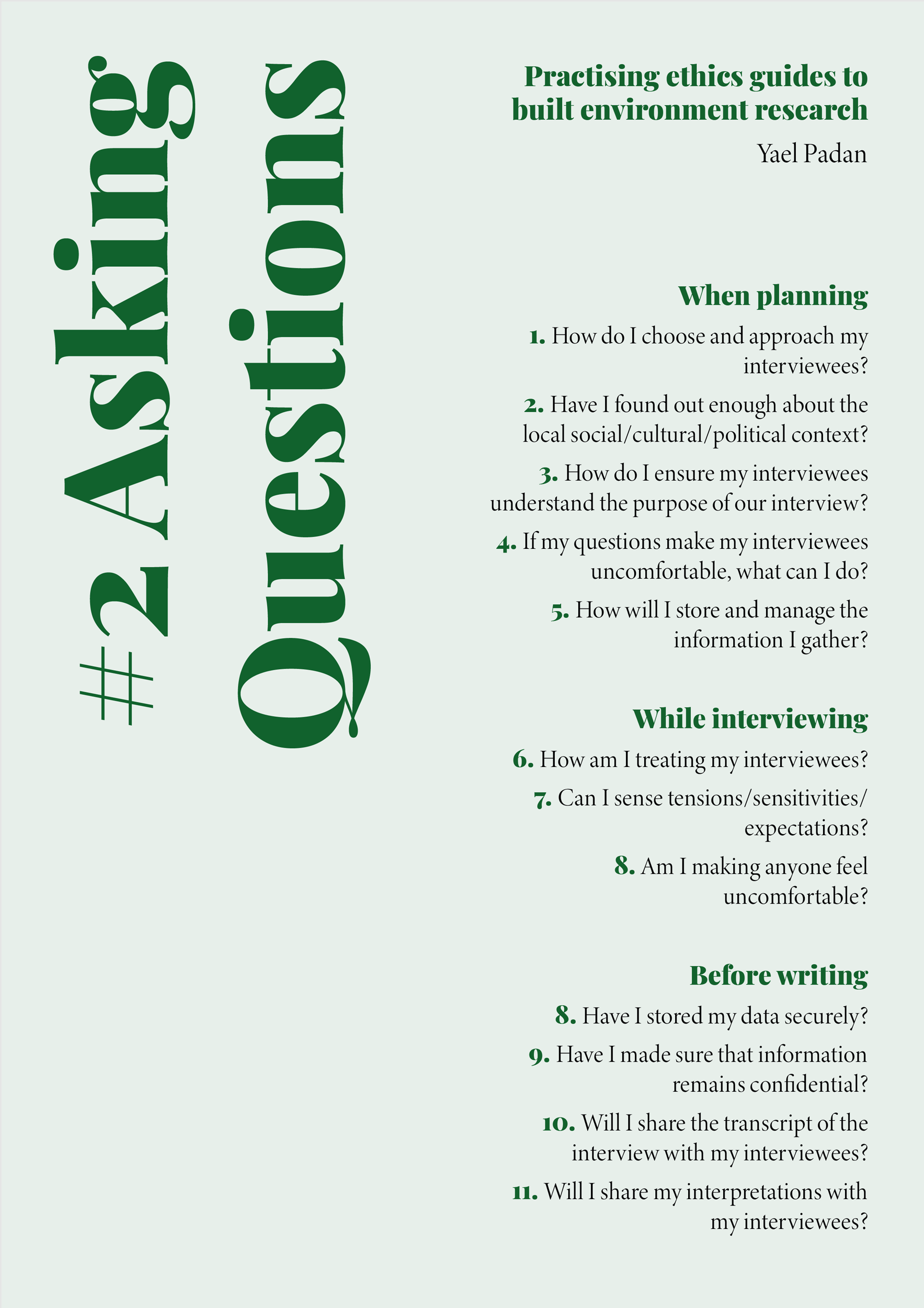

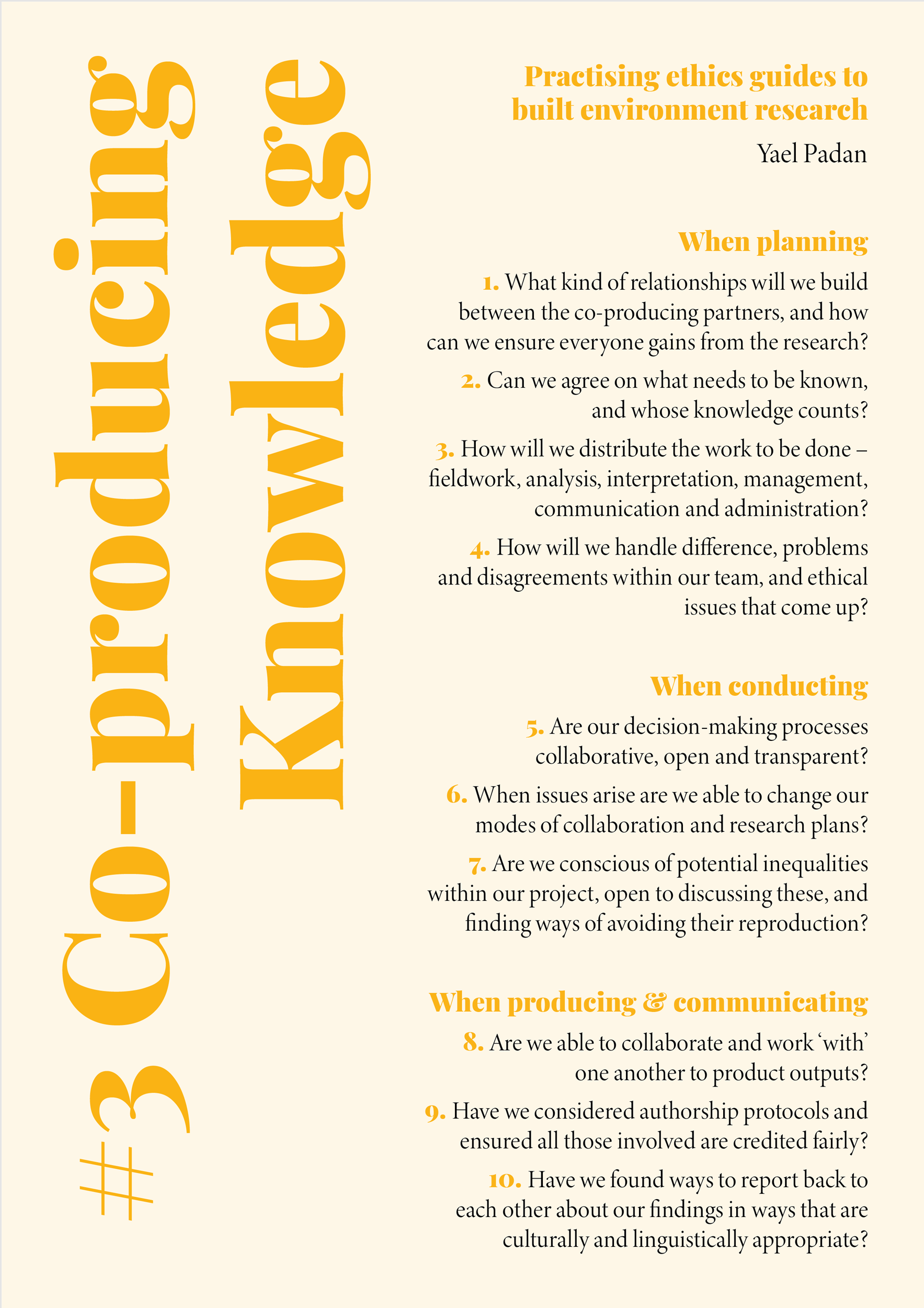

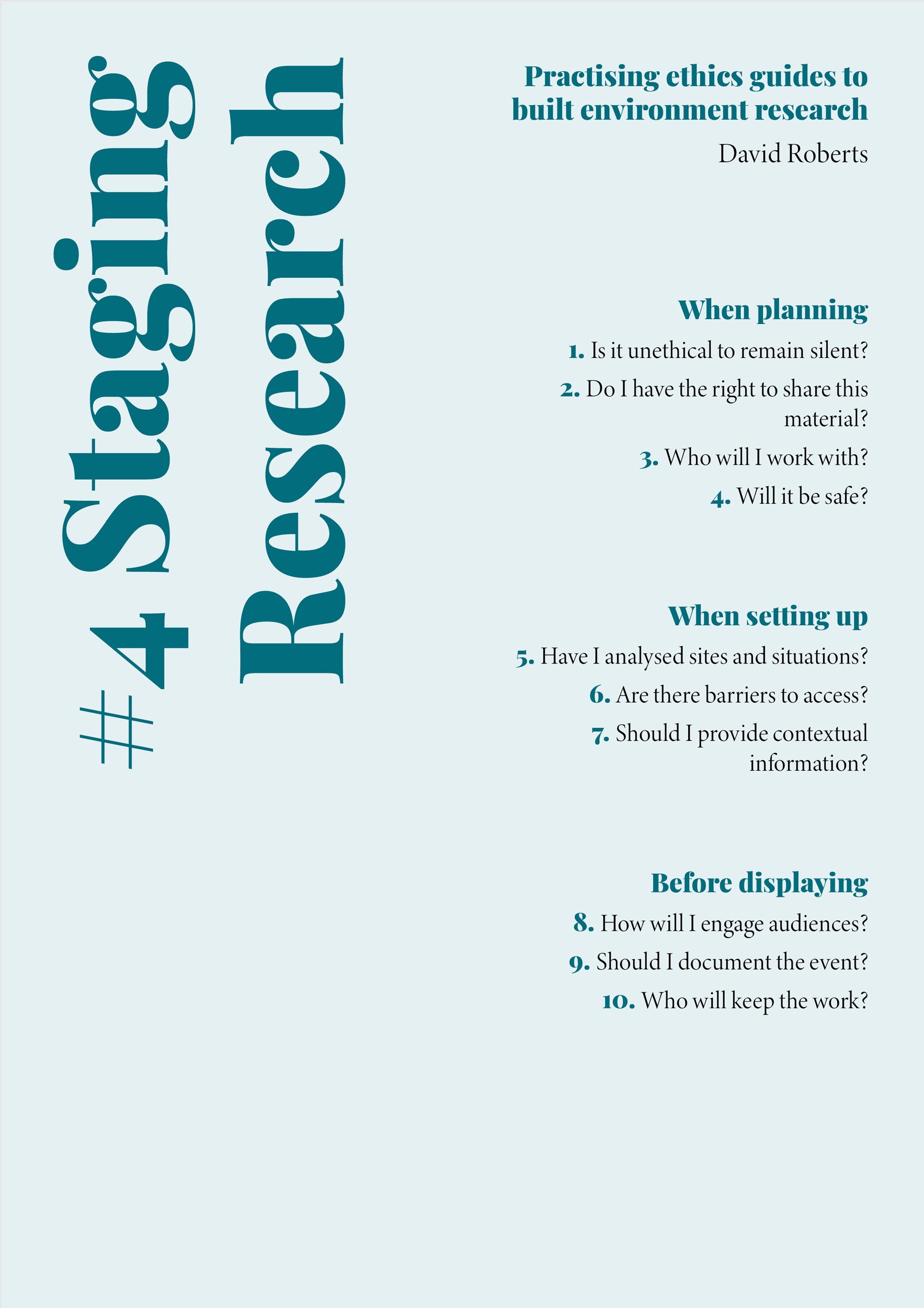

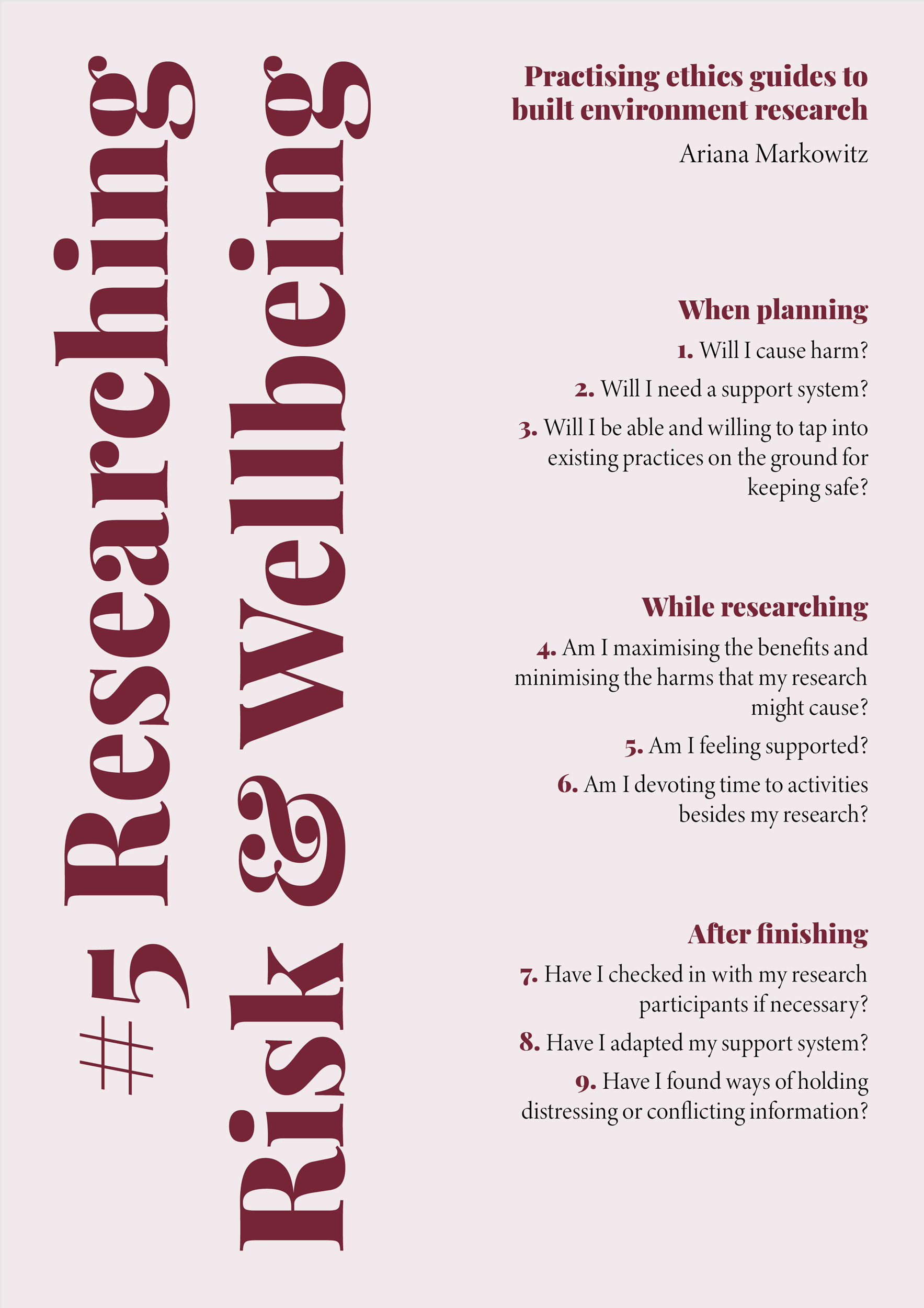

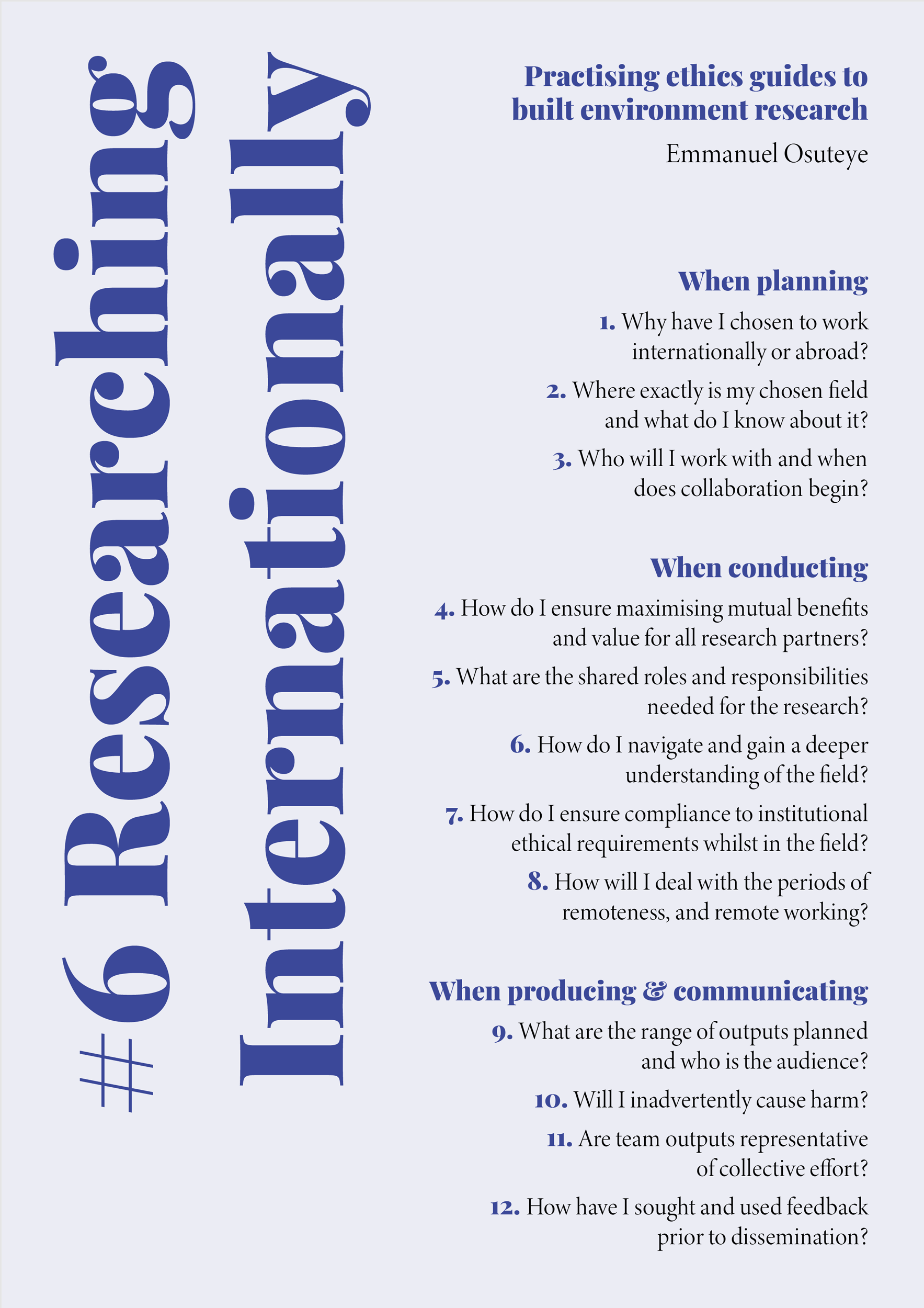

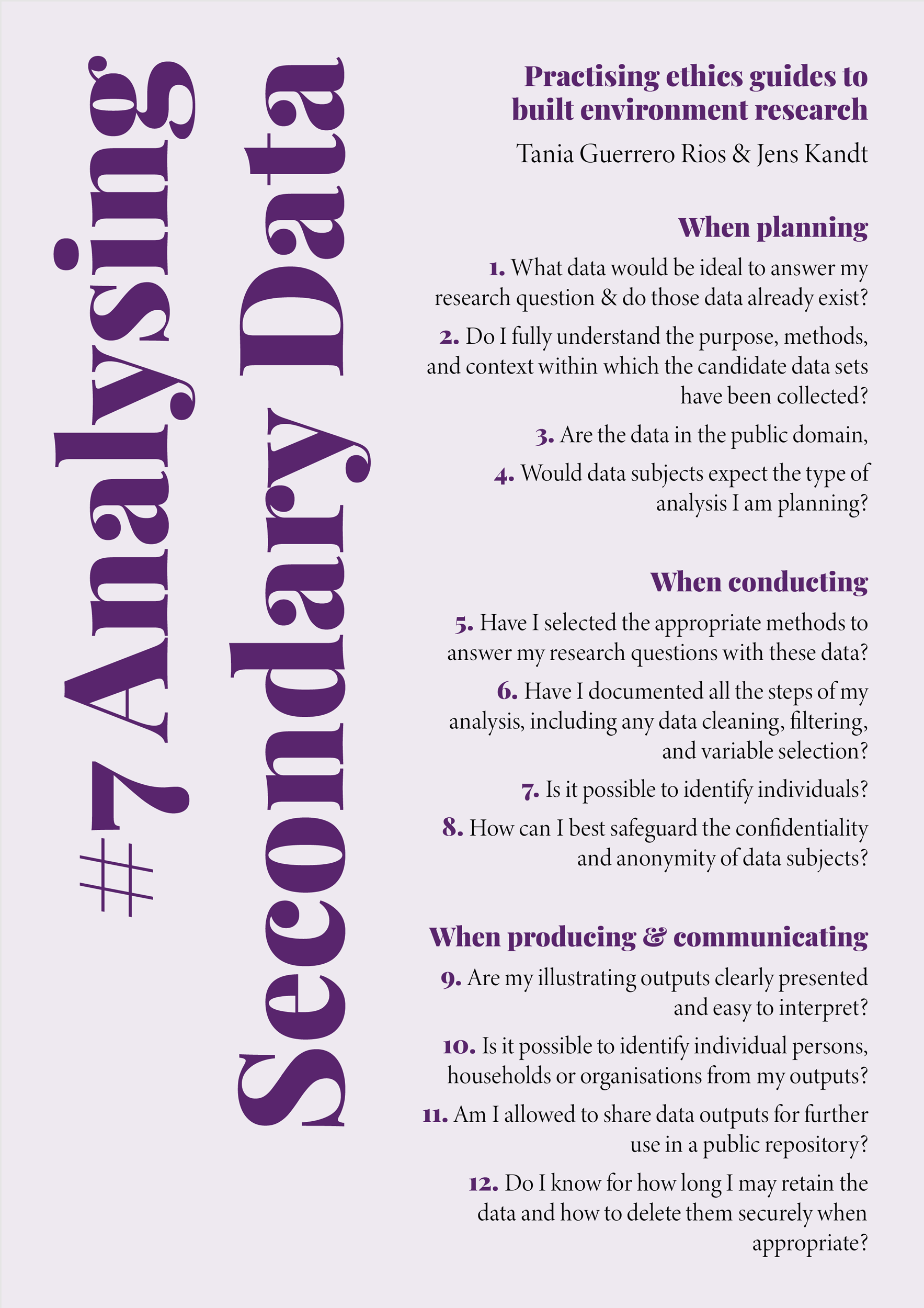

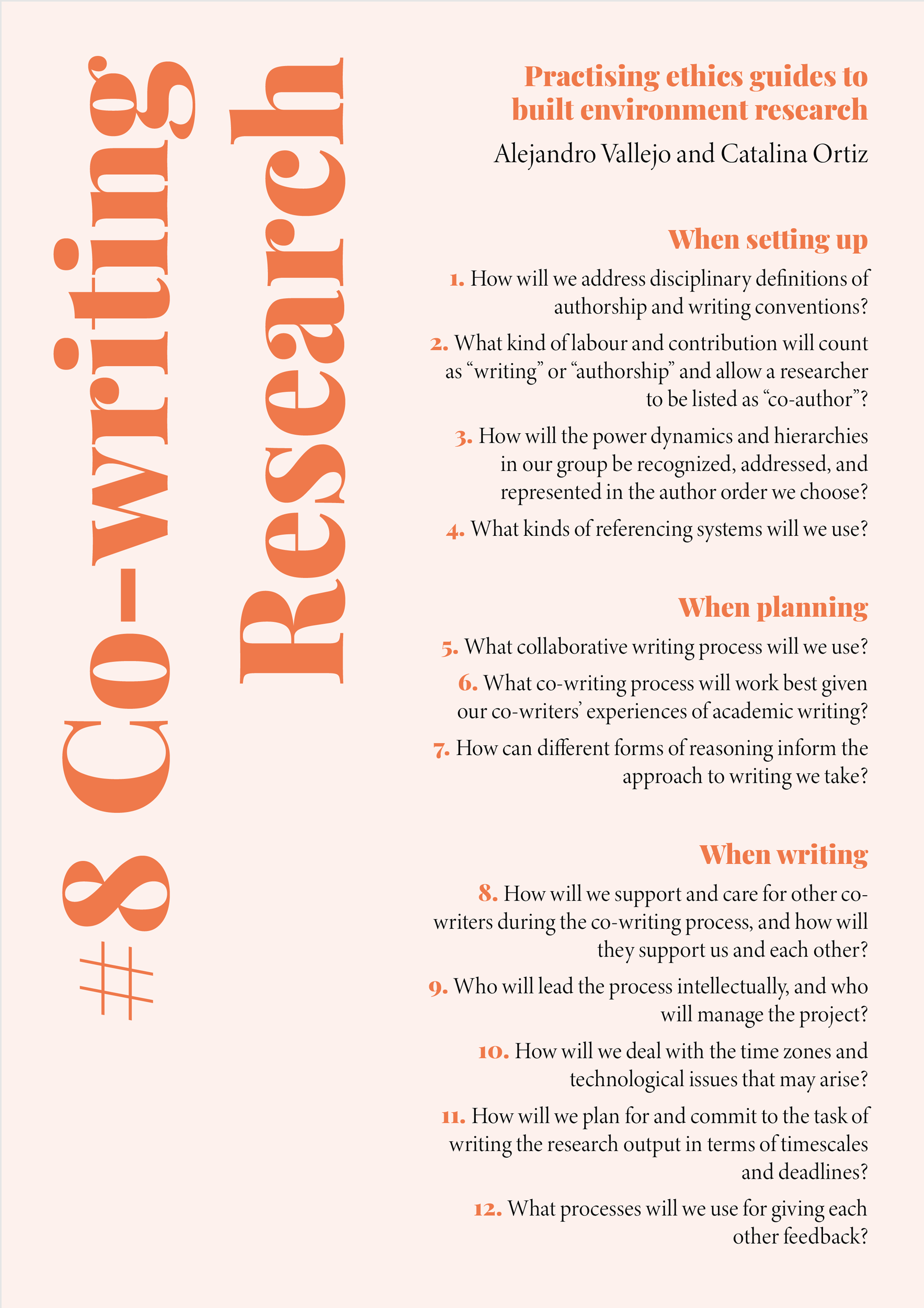

These self-reflexive questions form the backbone of Madison’s ground-breaking text Critical Ethnography (2005) and inspired the generative questions that open each of our Practising Ethics Guides tailored to the methods employed by built environment researchers, including: ‘Why have I chosen to work internationally?’; ‘Will I cause harm?’; ‘Am I making anyone feel uncomfortable?’; ‘Is it unethical to remain silent?’; ‘Am I alert to the history and power of this medium?’; ‘Are there barriers to access?’; and ‘Will I need a support system?’

As our aim has been to help readers practise their research ethically, from these opening questions I devised the format and structure of the guidelines to follow the path of ethical issues as they might arise during the development of a research process — from planning and conducting research, to communicating and producing outcomes. Each guide opens with a series of guiding questions, acting as prompts to reflect on the potential ethical considerations which emerge throughout a project, before, during, and after research has been conducted. The guidelines proceed to expand on the dilemmas and possible courses of action suggested by reflecting on the questions, illuminating the different ethical concerns they raise, and recommending actions.

Practising Ethics Guides were written by experienced researchers who guide their readers through the processes of negotiating the ethical dilemmas that can arise during a research project. For this reason, they focus on the different kinds of ethical issues practitioners might encounter as a result of using specific research methods and pay attention to the particular contexts and ways in which these methods are practised. When practising research, methods and context inform one another; we consequently consider this series of guides as embedded in a mode of applied ethics that is both situated and relational, bringing together forms of knowing with ways of doing.

Pia Ednie-Brown introduces Francisco Varela’s notion of ‘ethical know-how’ as a framework for considering how best to equip creative practitioners for the ethical dilemmas they will face, which recognises the situated nature of ethics in practice, ‘in harmony with the texture of the situation at hand, not in accordance with a set of rules or procedures’. Varela’s notion of ‘ethical know-how’ is a conceptual touchstone for iDARE, a project we have been in dialogue with since 2015. Drawing from Mencius, Varela proposes that rules and procedures ‘will always remain external to the agent, for they will always differ at least in some ways from the agent’s internal inclination’. Ethical know-how, by contrast, involves spontaneous, compassionate moral action sensitive to the particularities and immediacies of lived situations. To develop this disposition where immediacy precedes deliberation requires expertise gathered through a sustained journey of experience and learning:

And because truly ethical behaviour takes the middle way between spontaneity and rational calculation, the truly ethical person can, like any other kind of expert, after acting spontaneously, reconstruct the intelligent awareness that justifies the action.

Taking inspiration from existing research ethics resources, such as Susan Cox and others’ Guidelines for Ethical Visual Research Methods (2014) and IDEO’s The Little Book of Design Research Ethics, each guide sets out core ethical principles and includes a selection of further resources, along with questions and guidelines. The decision to include core principles — such as consent, confidentiality, and benefit not harm — was fundamental to our intention of developing and refining an approach sensitive to the institutional and conceptual, as well as the cultural, physical, and emotional challenges that can arise in the research process. Most of the guides refer to the three key ethical principles set out by University College London, as this is the context in which our own research took place, but throughout the guides we have also highlighted in bold other words, which refer back to a broader set of ethical principles found in philosophy that we discovered through our research; we have also referred to principles that were identified by our research participants in their lived ethical experiences, which have been included as part of the Practising Ethics project in the form of a lexicon.

To develop our guides and clarify what might comprise the most helpful framework for reflection and action, we studied a range of other models for ethical decision-making, including those generated by The Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University, the Framework for Making Ethical Decisions (2013) produced by Brown University, and the guidance of The Oral History Society. These hold in common a focus on the chronological sequencing of ethical research processes, but at times do not fully recognise the differences that particular research methods pose for practising ethics. In order to better navigate this relation between the universal and the particular or specific, we devised a template for writing a guide that included sections common to all guides, and other sections which differed depending on the method and context being addressed.

Since built environment research is as much about people as it is about places, in these guides people, both researched and researching subjects, are the focus of ethical practice. This includes the people who use and inhabit the places being researched, the people engaging with those places emotionally or spiritually even if they are not physically present, the people who design and those that build them, and the people who own or manage them. In addition, the guides consider the researcher as necessarily a key person or actor who devises the research approach, becomes a participant in the place where they gather data, and determines how to interpret that data and what to do with it.

The guides put into practice the definition set out by Susan Banks and others that ethics is about the kind of lives people may lead, considering what actions may be right or wrong, and which qualities of character we might develop, but most importantly, the responsibilities we have for each other and our ecosystem. They foreground process over outcome; because both people and research can be unpredictable, researchers need to be prepared to navigate unexpected situations and high expectations with limited time. Noting how even the best-laid plans often go awry when they come into contact with reality and real people, the guides emphasise the importance for researchers to put systems in place to support them throughout their process, minimising harm to those they are researching and participating with, as well as themselves.

It is important to note that the guides are not exhaustive and are not intended to address all the possible situations to be faced, particularly for research on sensitive topics or in places experiencing violence or instability. But we argue that learning from the experiences of others can help gain the ability to reflect on what is encountered, and to make informed decisions about the best way to practise research ethically. Insightful and imaginative research encompasses a range of sites, cultural contexts, and people, and there will always be a need for flexibility and care.