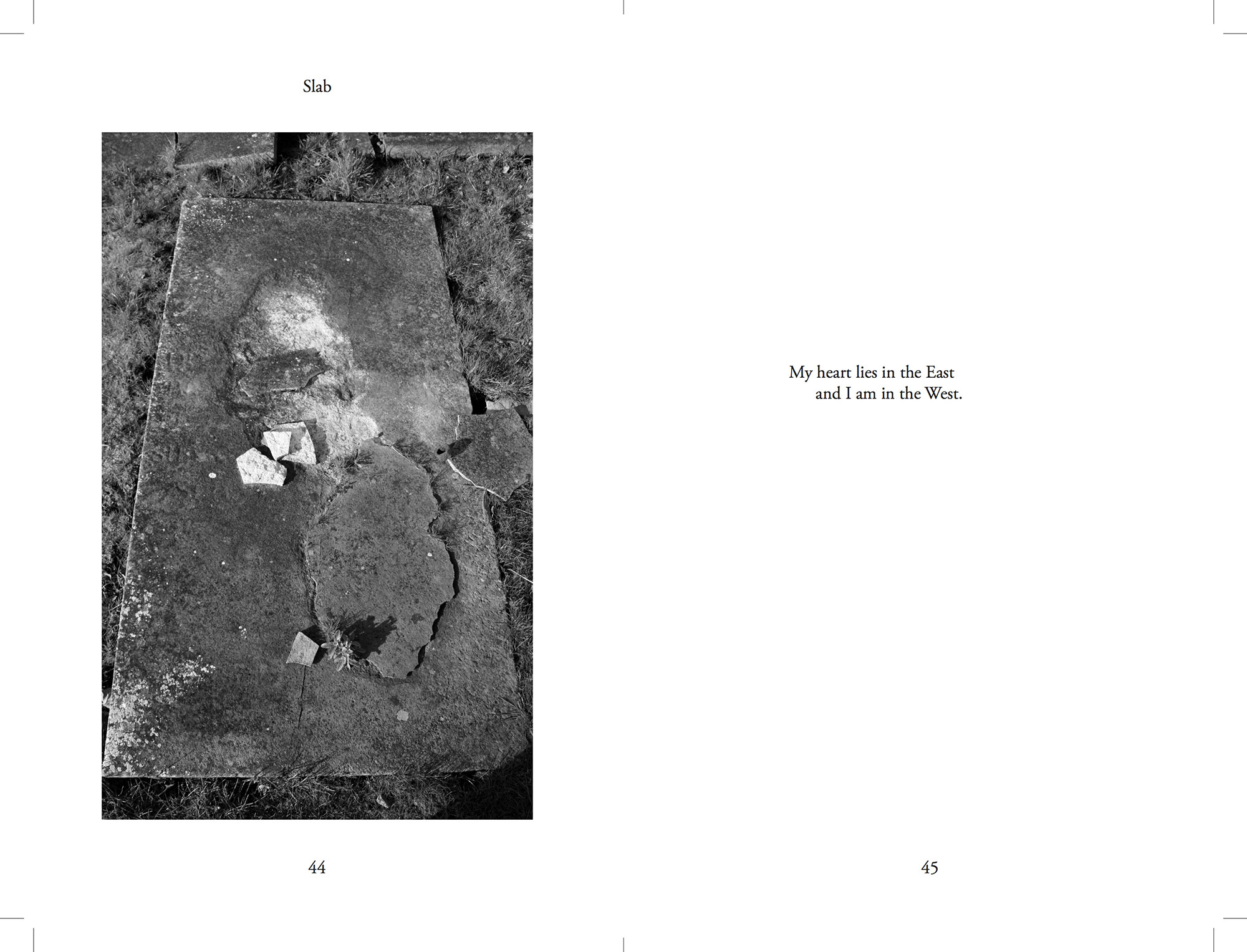

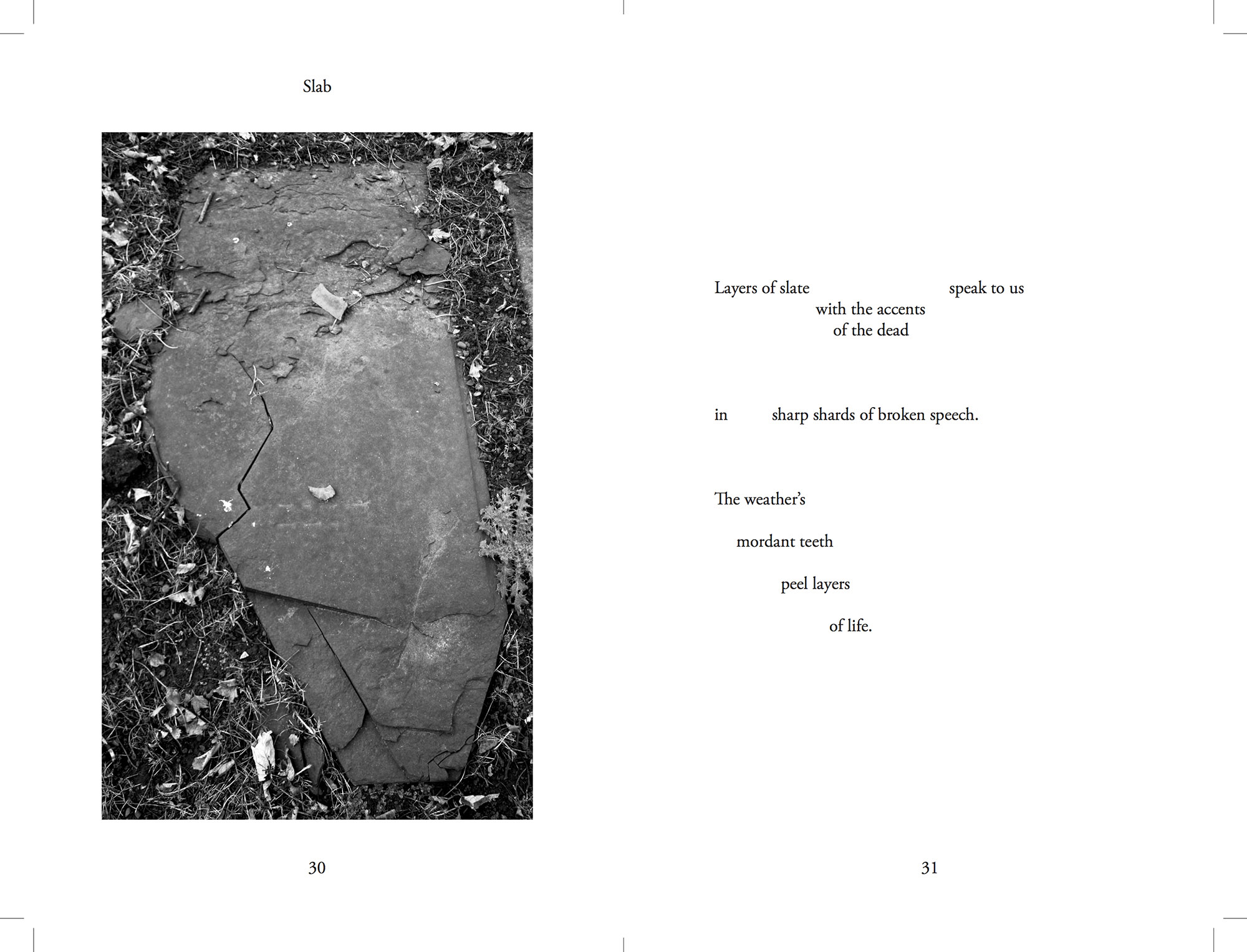

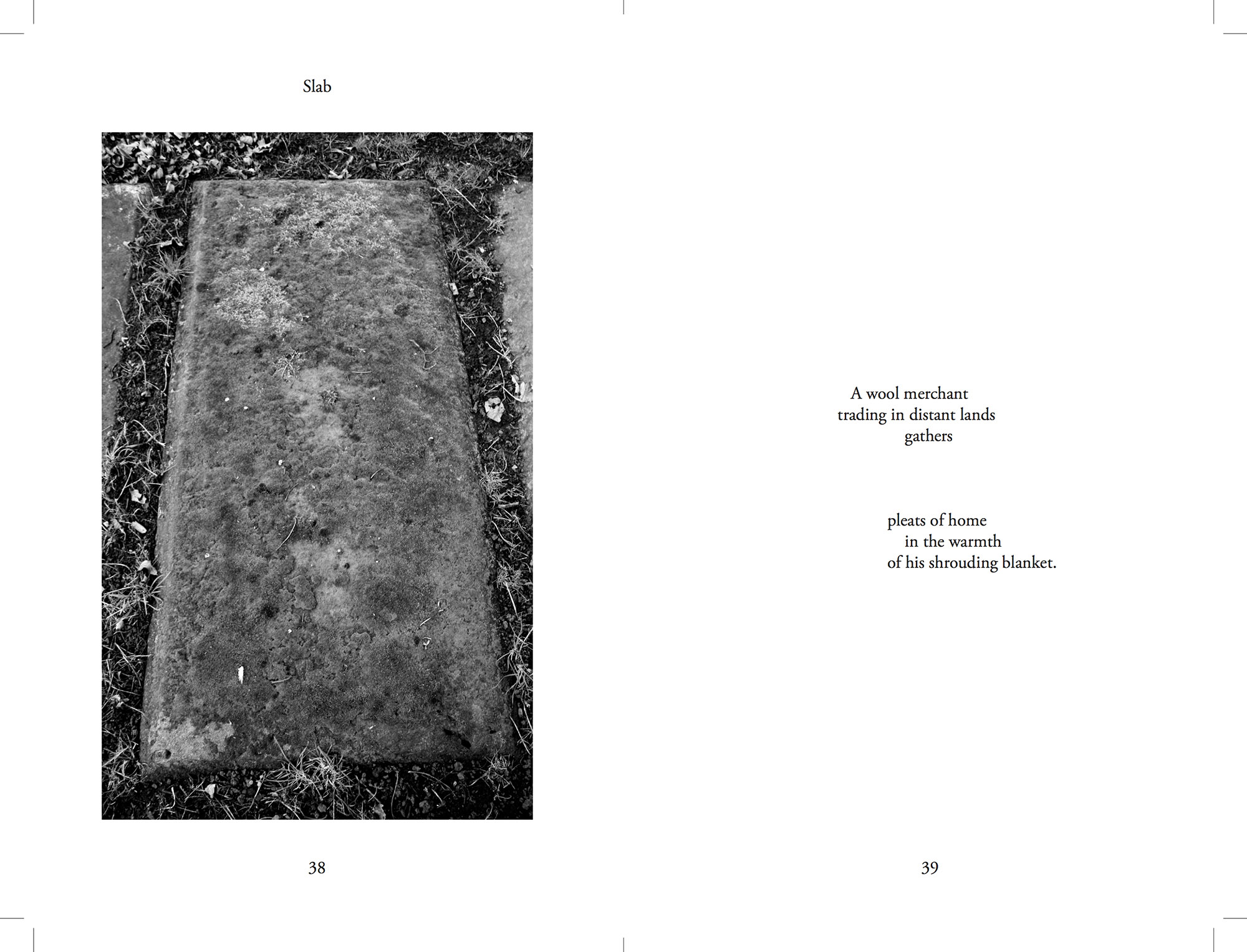

SLAB

Slab is a collection of concrete poems and photographs based on the Velho Sephardic Cemetery in which tombstones rest flat to the earth, wreathed in moss, shattered and absorbed into the ground.

The poems chart the history of the Sephardim, Jews forced from Spain, a land where Jewish and Arabic intellectual and spiritual life once flourished together, a history of co-existence that has been muddied and denied. Along with their scanty baggage, the only possession the Sephardim were permitted to carry was their language, Ladino, a combination of ancient Spanish and Hebrew. Those who headed west kept in contact with Spain and their speech evolved with Castilian, but those in the east were cut off, their speech frozen in ancient Spanish. The further they travelled the more porous their language became. Ladino retained its Hispanic base but relied on other languages to evolve and survive, borrowing words and fusing phrases together, legacy to their abandoned cities.

In parallel, the poems chart the history of my Sicilian grandparents who were sheltered and nurtured by this Jewish community three centuries later when they slipped into London as tailors. Like them, the last generation of Ladino speakers to have lived Sephardi culture rest in old people’s homes clinging to this ancient speech through the long centuries of concealment.

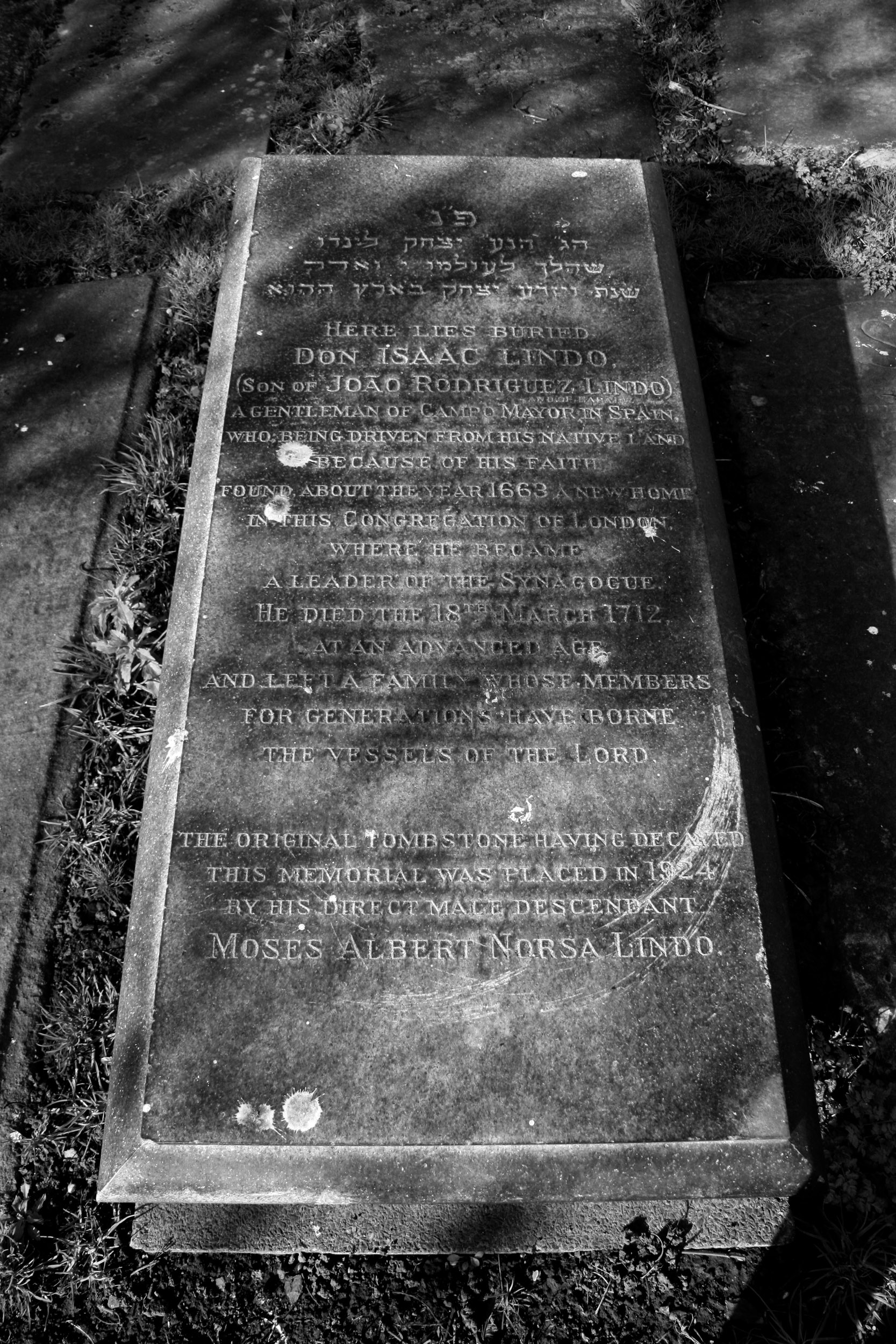

I wrote each tombstone a poem drawing from epitaphs and around the formal arrangement of Ladino konsežas, romanzas and coplas. Where full biographies existed, I selected key fragments. Where there is no clue to the stone’s identity, the text is as unreadable, scratched like slate, mottled like moss, concealing these histories once again. I delivered each poem on a single postcard to each room of Albert Stern Halls to students now living in the former Jewish old people’s home that surrounds the site. Each student received one postcard with a connection to one stone addressing the many forms of loss these journeys entail.

Excerpt

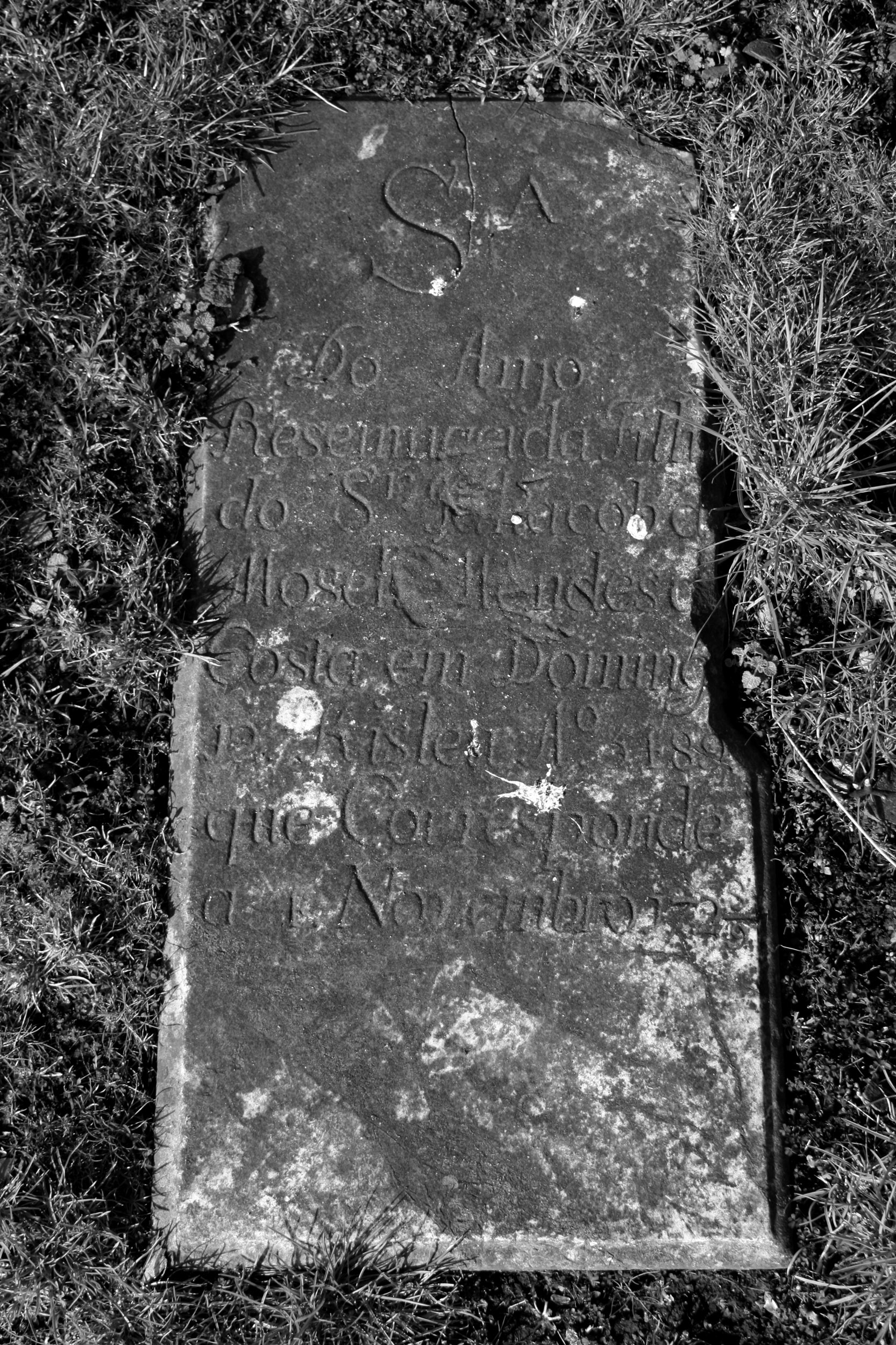

It is raining softly and I am not a trustworthy narrator. In the pale light I leave Mile End Road at the western fringe of Queen Mary College, where mattresses slouch in line by Stepney Fried Chicken and the veiled bus queue spills on to the blue cycle superhighway. I reach a pointed arch timber doorway on a high wall beyond which lies a cemetery, a small plot not even an acre marked by over a thousand graves, enclosed on all sides by student halls and garden walls of terraced cottages. The tombstones rest flat to the earth, not one with an upstanding tablet. In twenty-three rows they keep close company, bare stone or wreathed in moss that clings to this old world, full oblong or shattered and absorbed into the ground, ties of blood woven together by the roots of sixteen trees that split and swallow manuscript. Some inscriptions are still legible today, cut in Portuguese and Hebrew, some Spanish, few English, recording little more than foreign names and dates and the rare indulgence that paints portraits of this community in quick strokes, ‘the bird catcher’, ‘sweet poet’, ‘maiden’, ‘son of the harp player’. Others are worn plain until this rain collects and fills faint hollows, and for a moment their ancient epitaphs gleam, complete, then are gone, overflowing as tributaries branch and blot from word to word when, flooded, the stones become a mirror...

In 1492, Christopher Columbus was preparing three ships on the eve of his famous voyage, noting in his diary the ‘fleet of misery and woe’ as the last Jews spent their final night on Spanish soil. Hundreds of thousands were forced from their homes to escape the fires of the Inquisition and tortures of the Question Chamber. These were the Sephardim, one of the two great groups into which Jews are divided, deriving from the Hebrew for Spain, a land where Jewish and Arabic intellectual and spiritual life once flourished together, a history of co-existence that has been muddied and denied. They left this ‘golden age’ and resettled into two distinct civilisations. One route led eastward to the world of Islam, from Morocco across North Africa to Palestine, and from the Mediterranean’s northern shores to the Balkans. The other led to the Christian west, to Portugal where they were soon forced to convert or flee onwards to Holland, Southern France, Hamburg, the Americas and England.

Along with their scanty baggage, the only possession the Sephardim were permitted to carry was their language, Ladino, a combination of ancient Spanish and Hebrew. Those who headed west kept in contact with Spain and their speech evolved with Castilian, but those in the east were cut off, their sweet and mild speech frozen in ancient Spanish. The further they travelled the more porous their language became. Ladino retained its Hispanic base but relied on other languages to evolve and survive, borrowing words and fusing phrases together, legacy to their abandoned cities. Joined with too much Hebrew, Ladino was thought of as overly conservative; with too much Italian, pretentious; with Greek, funny and rather vulgar.

The Sephardim carried the culture of this vanished land with them wherever they found refuge, recreating the streets and atmosphere of Spain in their juderías, Jewish quarters. The floors of synagogues in the Caribbean were often covered deep in sand to recall their past when ‘footsteps had to be muffled to avoid detection’. Ladino offered playful freedom through cryptic puns and discreet jokes to cope with living in between two worlds, and its literature held them close to their troubled past. Sephardi poetry found great popularity in everyday life, often introduced to guests after a leisurely meal, and even in passports. They wrote of their lost land though konsežas, romanzas, coplas, where different languages intertwine so tightly that the speaker is unaware they are separate, and sayings become so separated from their origins that distance from their homeland mirrors distance from the text. ‘Good words split stones’ one proverb suggests. People journey, words journey.

Of the Sephardim who travelled west, around seventy had settled in London by the seventeenth century living as marranos, attending Mass in a Roman Catholic chapel but in their hearts holding firm to the faith of their upbringing. It was not until 1656 that they dropped all disguise. The burgeoning congregation petitioned for two sites of ritual, a synagogue in a converted house on Creechurch Lane in the City of London and a burial ground, Beth Haim, ‘House of Life’, in Mile End where we have escaped to. It was then an orchard of forty fruit trees. It is now known as the Velho, the ‘oldest’ known Jewish cemetery in Britain, which opened in 1657 and closed a century later.

The first Sephardim who settled in London kept themselves as inconspicuous as possible. At this time England was beginning its devastating Imperialist expansion through maritime trading, and within narrow streets a little world was carved by Jewish merchants, ship owners and gem importers, alongside penny-barbers, tailors, sugar-bakers, cravat-washers, diamond polishers, lemon-men and domestic servants. This community administered their own affairs and laws. They offered support to the poor migrants who had joined them in London, setting up societies for: apprenticing, circumcision, comforting mourners, dowering poor brides, clothing the destitute, supporting female orphans, tending the sick and burying the dead.

It was this same Jewish community that three centuries later sheltered and nurtured my granddad when he slipped into this city as a tailor, offering him work as an assistant in Savile Row. Wary of this Sicilian Catholic in their midst, Rabbis unpicked his suits to assure no mixing of wool and linen in breach of the Torah. His committed clients, merchants and diamond dealers, helped this man of little means and education but of unusual goodness, to open his own shop and train his wife and children in his craft.

While my granddad met clients, my grandma was a tailor’s assistant’s assistant, stitching and mending from home while caring for my mum and her brothers. But it was in this new shop that she found her calling and her voice, holding her own among the merchants and dealers. Since my granddad’s death, she has once more become cautious to speak English in public, retreating back to a handful of Sicilian songs and rhymes, and as memory and anecdotes grow faint so too does my childhood.

Like her, the last generation of Ladino speakers to have lived Sephardi culture rest in old people’s homes. As compulsory education rolled out, Ladino faded under each official language and was almost entirely wiped out in the Holocaust. It survived by virtue of Jews living outside of Europe, often in Islamic societies where women were isolated from education and trade. They clung to this ancient speech through the long centuries of concealment, a maternal language preserved in songs that accompanied cleaning, cooking and needlework, repeated to cradling babies, marrying couples and grieving relatives, tying them to tradition and binding the scattered.

However small and fragile, Ladino lives today in the work of great Sephardi thinkers, Primo Levi, Jacques Derrida and Baruch Spinoza. Among the works of Spinoza that have been preserved, there is only one passage in which he makes use of the mother tongue of Sephardim. It is a passage in which he explains the meaning of the reflexive verb pasearse ‘to walk-oneself’ in which agent and patient, subject and object, potentiality and actuality, are one and the same person in ‘a threshold of absolute indistinction’.

To walk-oneself. I am taken back to the first time I set foot in the Velho cemetery in Mile End ten years ago. I was a different person then. I walked among the undulating pavement of gravestones and wanted to learn what was omitted from the simple lines of restrained epitaphs. I rummaged in archives, collected facts, proverbs, folk-tales and poems, often in Ladino to piece together these stones.

In the cemetery, the small and great are buried alike, lowered into the grave with feet facing east ‘so that they may rise and walk to the Holy Land’. Some images carved into stone still sing; roses, scores of skull and crossbones, small stones with winged cherubs for those who died in infancy, and the occasional arm and hand reaching from the clouds to fell a tree, motif of a life cut short.

I placed hundreds of my fragmentary notes across the cemetery, thoughts held safe to slabs by pebbles. I began to write poems constructed around this work and found phrases sprinkled across the burial ground, each reflecting an aspect of the culture of people within these low walls and their kin beyond the seas. During this obsessive act, the characters of these histories seemed to mirror the character of the stones. I wrote each tombstone a poem. I started with a piece of related archival text, which I layered with my own emotional response. Some of the formal arrangements followed those of Ladino poems, while others echoed appearance.

Where full biographies existed, I selected key fragments. Where there was no clue to the stone’s identity, I let the tactile nature define the poem. Where slabs were unreadable, the text is as unreadable, scratched like slate, mottled like moss, concealing these histories once again.

I delivered each poem on a single postcard to each room of Albert Stern Halls to students now living in the former Jewish old people’s home that surrounds the site. Each student received one postcard with a connection to one stone. The numbered poems reveal the location of the tombstone. The reader engages in a symbolic act of unwrapping history, untying threads, uniting the viewer, the stone and their shared history.

I came here today to reread the poems I wrote ten years ago in the shadow of my granddad’s death. But when I rehearsed my words they seemed like strangers. I was raised a Catholic and when I wrote these poems my faith seemed a quiet constant, but it was soon to waiver and wane without my granddad. Underneath them is a turmoil - the many forms of loss that those journeys entail. The Sephardim were forced to conceal the faith of their upbringing but I chose to reject mine. Through such changes, whether forced or chosen, can we still be the people that we were?

Pasearse. To walk-oneself. I walk myself through the cemetery now, my other self of ten years ago my companion, faithless and faithful in step. We tread softly around stones. I see my other self with clarity in these poems. I see my granddad too. He passed on more than my Roman nose and thick hair. When I wrote these poems I saw in this interred Jewish community the same charity flowing from the wellspring of faith that their descendants passed on to my granddad. It was in his faith that he gave himself unconditionally to me and to others, in generosity too often unreturned. I feel I am breaking the bonds of my upbringing as I stand beside myself here, an unbeliever. I fear that I will never find the certainty and goodwill I so admire, but hold to a belief that what he left in me is more important to uphold than the opportunity to see him in life hereafter.