Manifesto Workshop

[Excerpt]

I would like to begin with an exercise. On your seats you will find a sheet of discordant poetry, a chorus of values, each stanza composed from the manifestos of different architects, artists and activists.

I invite you to each contribute to this exercise with your voices. I would like us to read every line together like a devoted congregation following a performance, or at prayer, or in protest. Ready? I will keep time.

[Architecture must] always be an exploration not a confirmation

(Alsop, 1993)

not a tool for imperialism and subjugation, not a means for aggrandizing the self,

but a vehicle for liberation and joy

(Black Reconstruction Collective, 2021)

I am not willing to get over histories that are not over

(Ahmed, 2017)

The architect’s job is not to propose ideal models for society,

but to devise spatial equipment that the citizens themselves can operate

(Kurokowa, 1977)

Everyone should be able to build.

We must face the risk that a crazy structure of this kind may later collapse,

and we must not shrink from the potential loss of life

(Hundertwasser, 1958)

Architectural education must be as much about unbuilding as building

(BREAK//LINE, 2018)

We build connections, conduits, channels, tentacles, and rhizomes,

converting and repurposing structures of power

(FAAC, 2018)

Expressive awesomeness!

(Jones-Hogu, 1973)

Any new building ought to commemorate the nature

that had to be destroyed because of it

(Hasegawa, 1991)

No one is participant only or designer only.

As people work together to heal their places, they also heal themselves

(Van de Ryn and Cowan, 1995)

We affirm our will to act to change the capitalist and patriarchal world

which puts the interests of the market before the rights of people

(Nyéléni, 2007)

Art is the practice of taking a position towards the world

(Azzawi, Al Turk and Al-Nasiri, 1969)

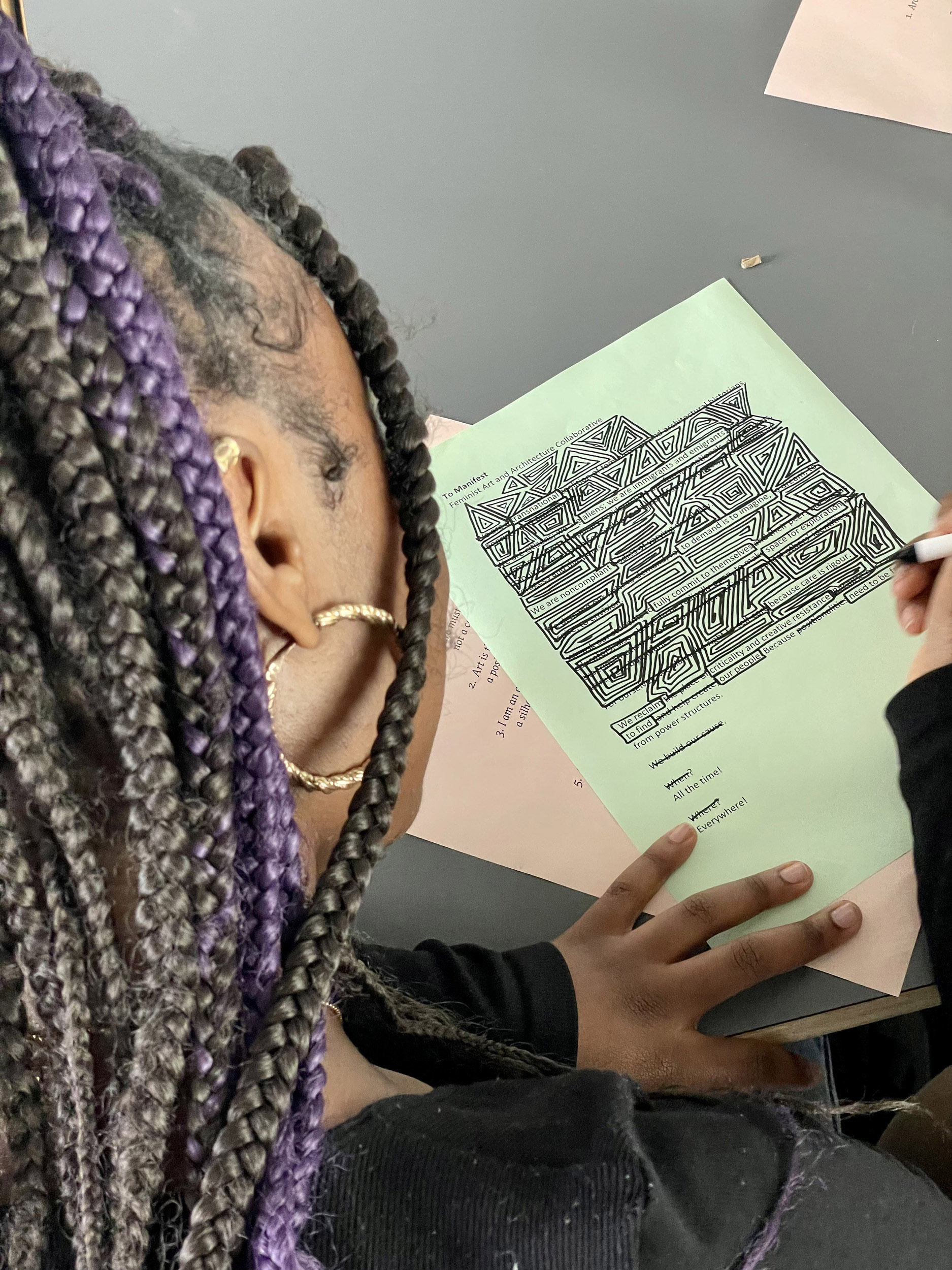

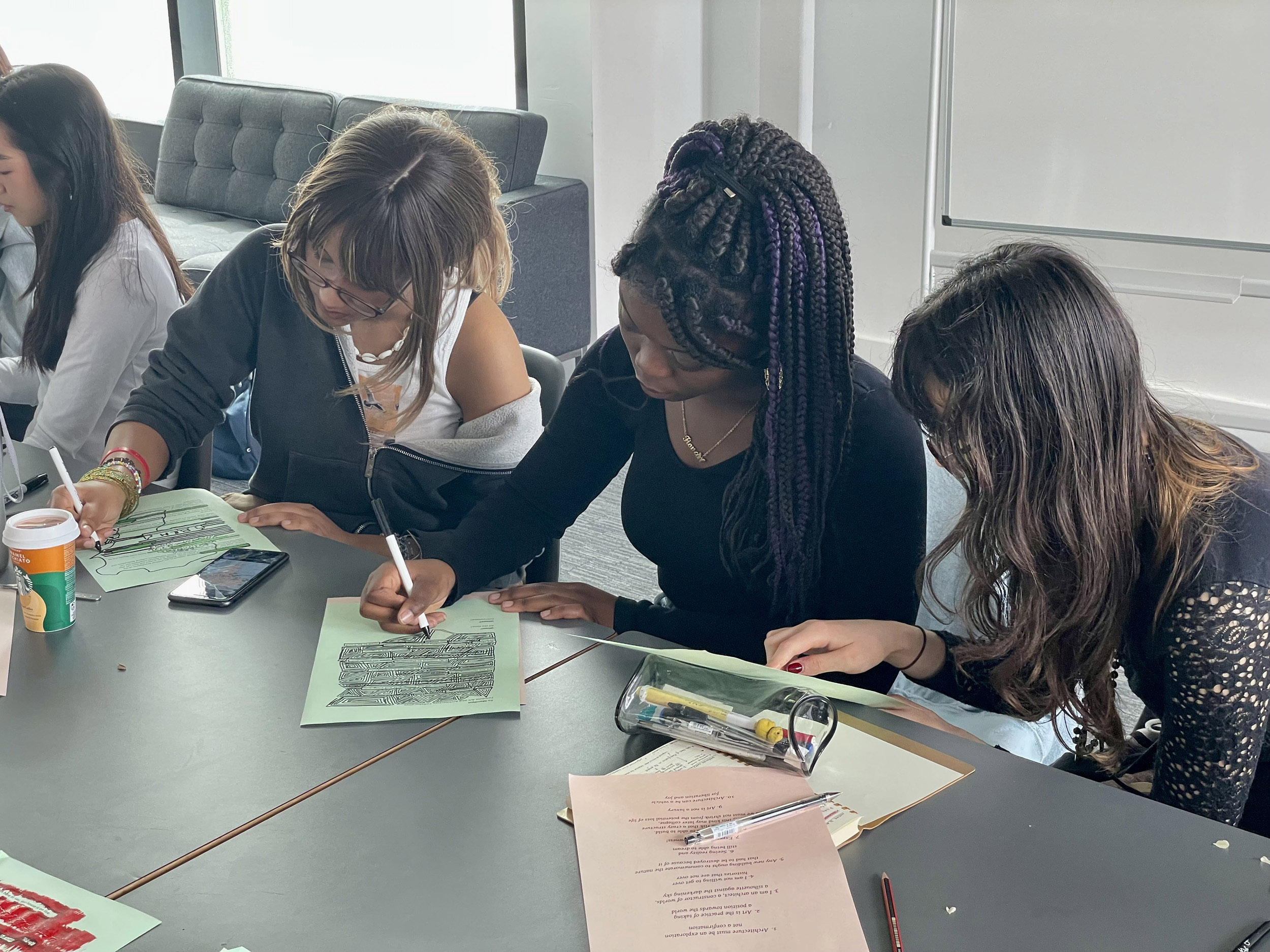

The manifesto chorus ushers in an unexpected atmosphere. The studio hush is broken with hesitant speech, skittish laughter and furtive smiles as students accustom to a class which calls upon their voices and compels them to speak a depth and range of issues and positions that inform architectural inquiry and practice. This first exercise is an abrupt introduction to a different way of being and learning together and, as such, may require some calming and coaxing, enthusiasm and encouragement to build participation.

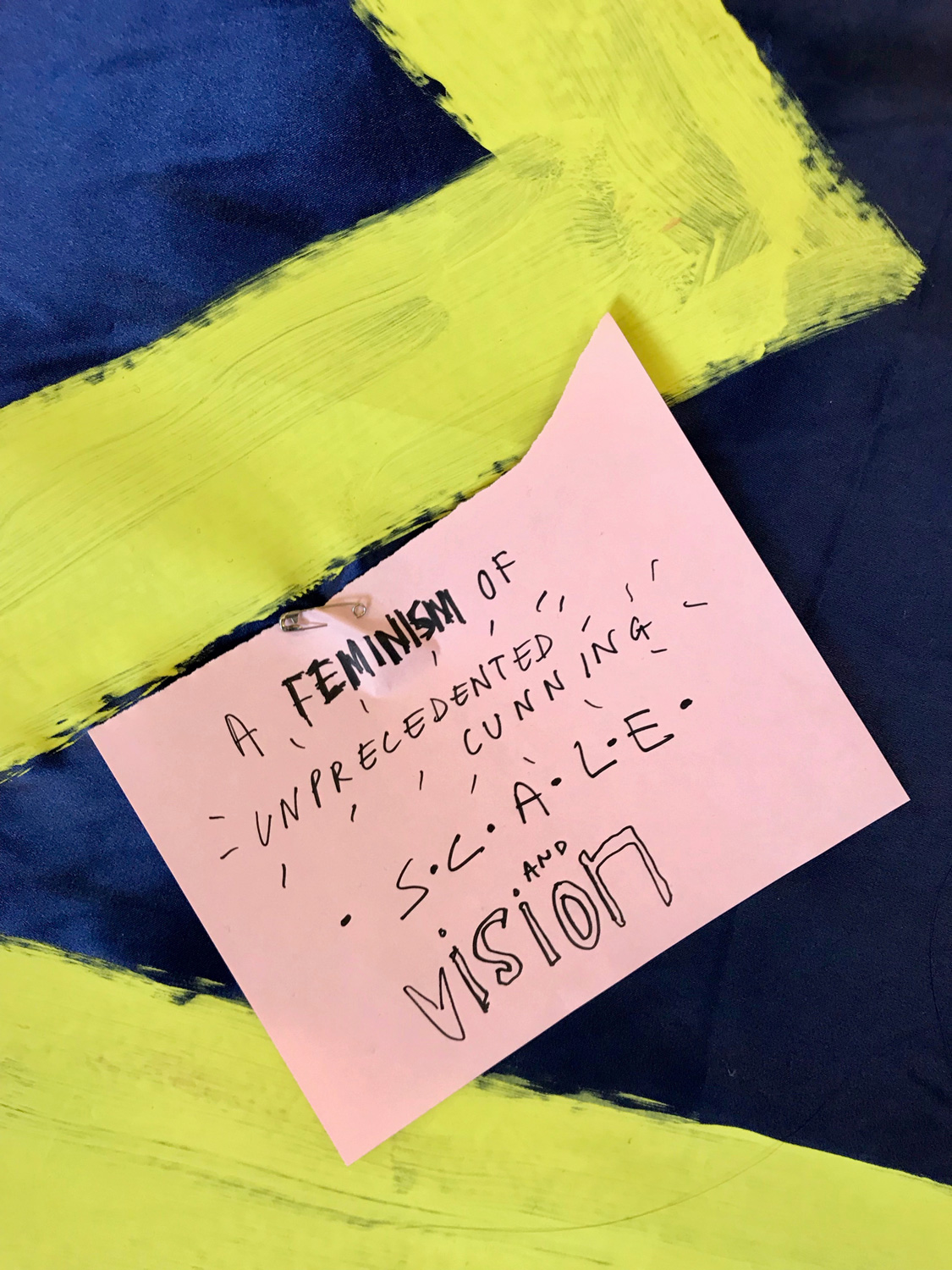

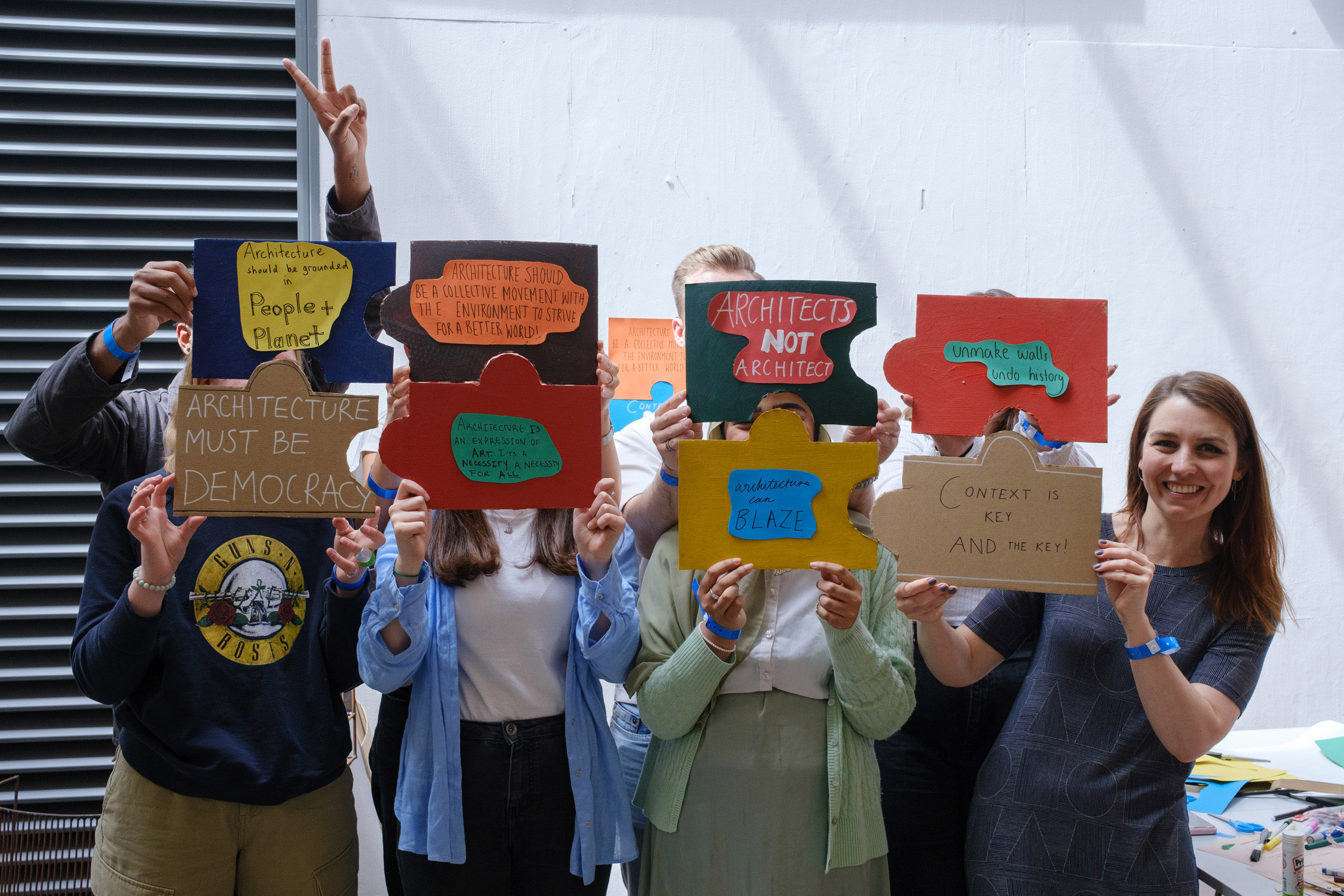

I run workshops on debating and drafting manifestos as a means to introduce emerging and established spatial practitioners to the range of ethical issues and positions that inform architectural inquiry and to articulate the practitioners they seek to become. I have introduced manifesto writing workshops to Bartlett School of Architecture, Central St Martins and Aarhus School of Architecture and as part of Break//Line with Miranda Critchley for Fast-Forward Feminism (Roberts, 2020).

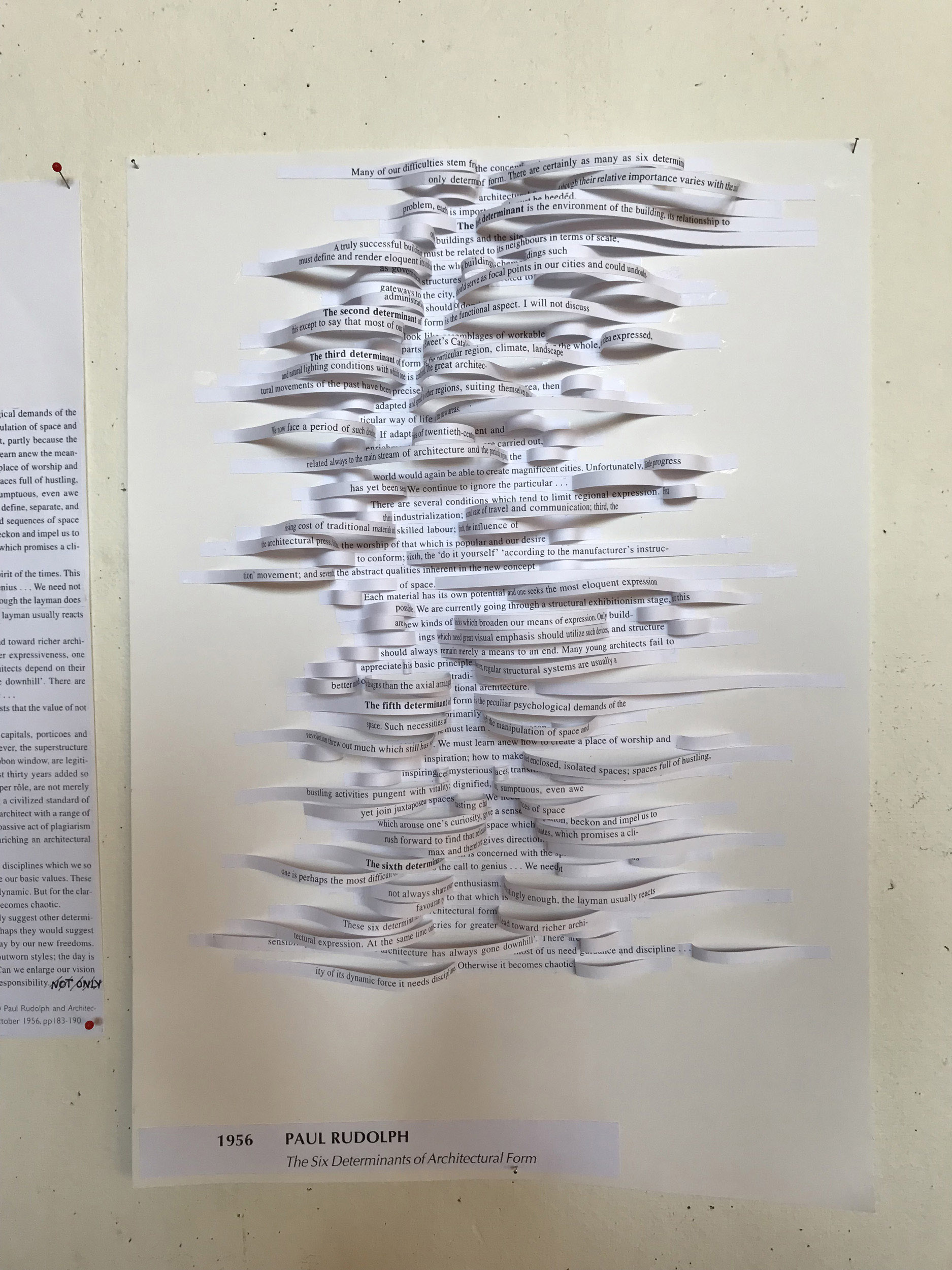

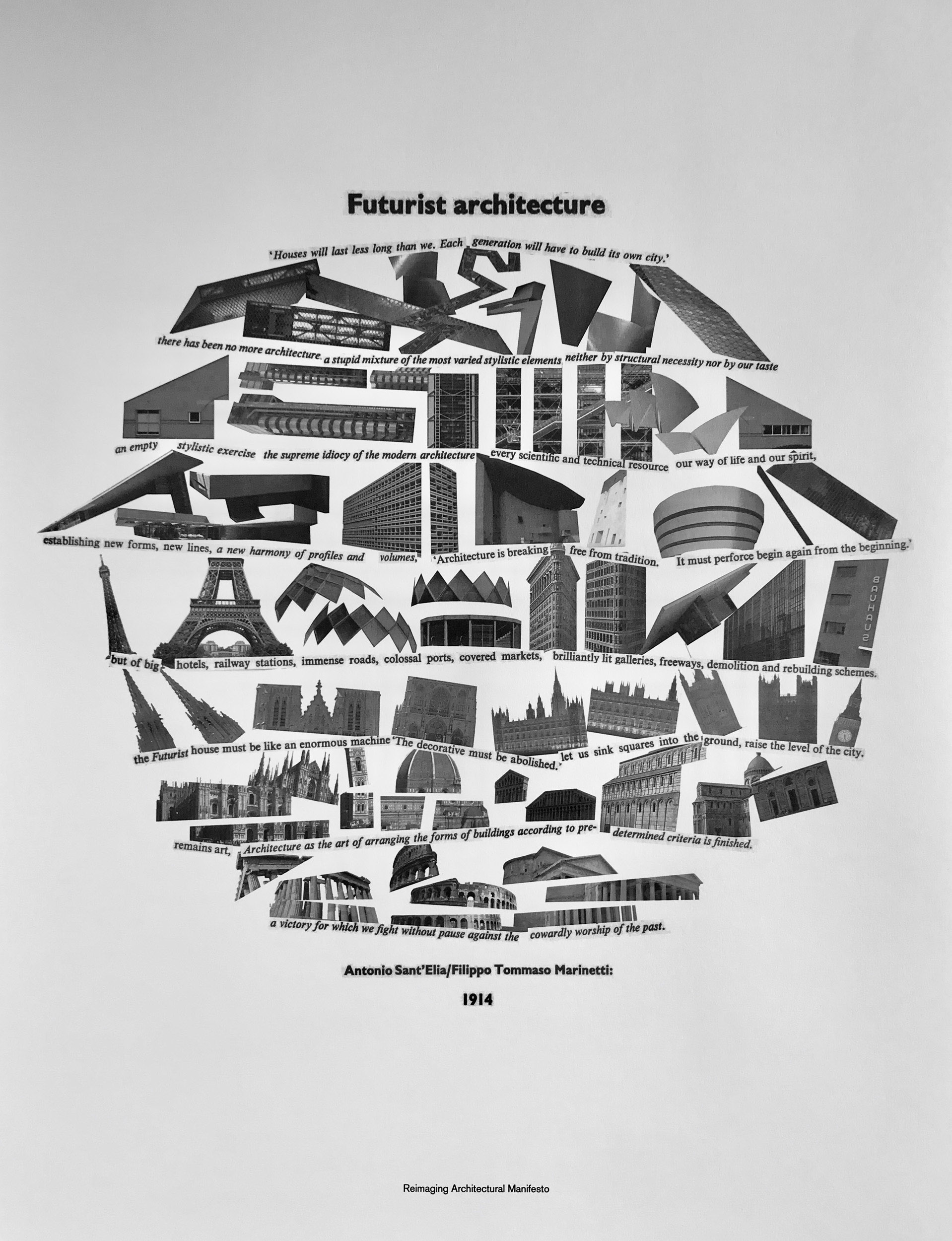

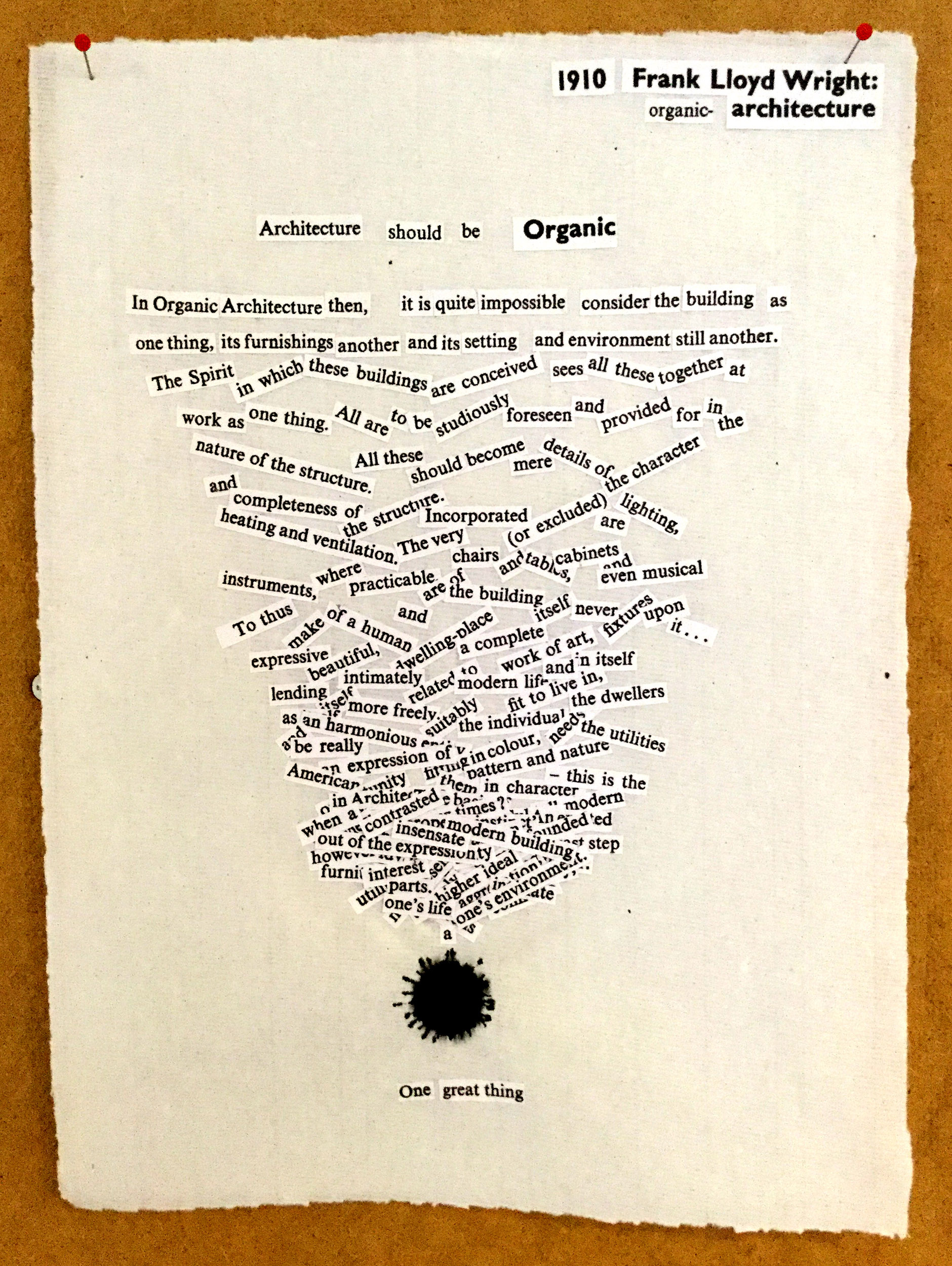

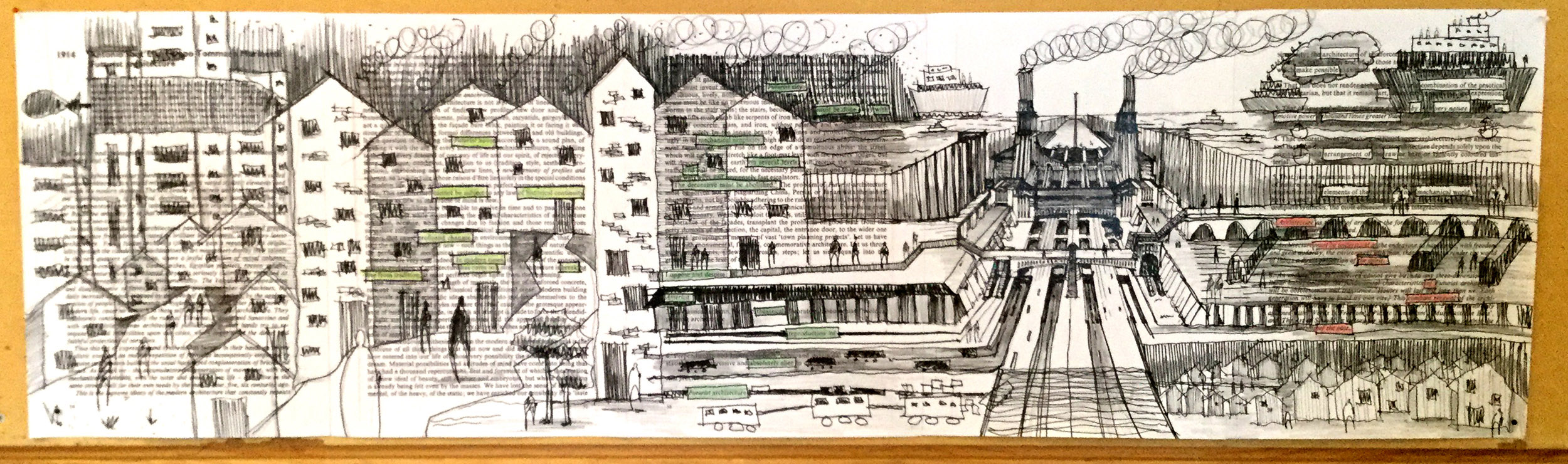

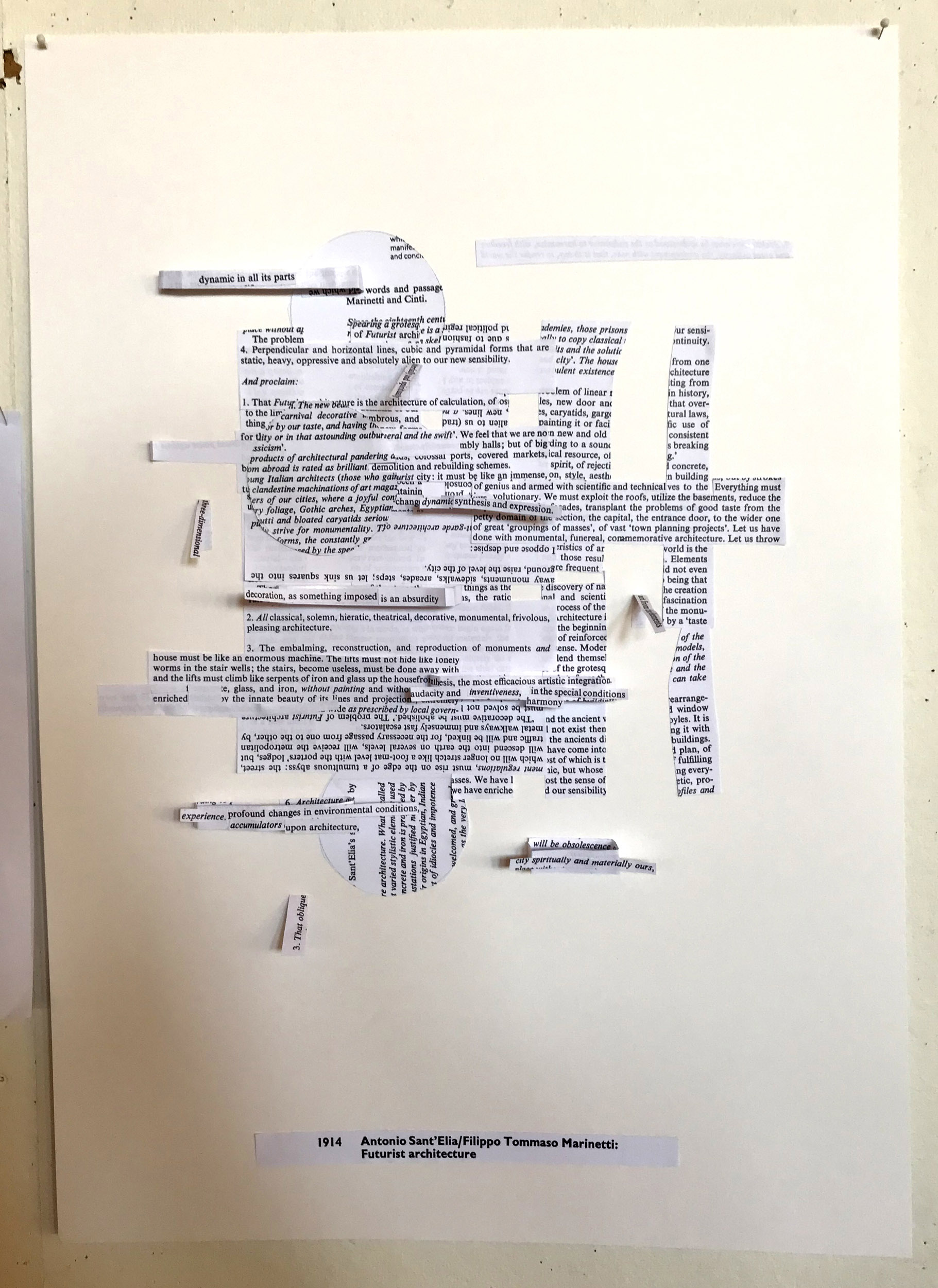

Manifestos have played a powerful role in architecture and urbanism over the past century. The architectural historian Beatriz Colomina argues, 'the site of self-invention, innovation, and debate', where 'even buildings themselves could be manifestos' (Colomina, 2014). As well as 'an indispensable vehicle for setting transformative architectural projects in motion', Craig Buckley warns how manifestoes 'have also been associated with some of the more problematic elements of such vanguard positioning, from hyperbole, exhortation, and naïveté to misogyny, racism, and sympathies for fascism' (Buckley, 2015). To write a manifesto, therefore, is no simple task.

My workshop involves six stages: setting out contexts and concepts, negotiating content, configuration, and confrontations, before performing a group concerto. We begin by discussing the contexts of our writing and how these aspects shape its principles and purpose. At a time of climate breakdown and biodiversity loss, systemic social injustices and inequalities, there is an ethical imperative to move beyond architecture's Western-centric bias, the narratives and concepts we perpetuate (Tayob and Hall, 2019).

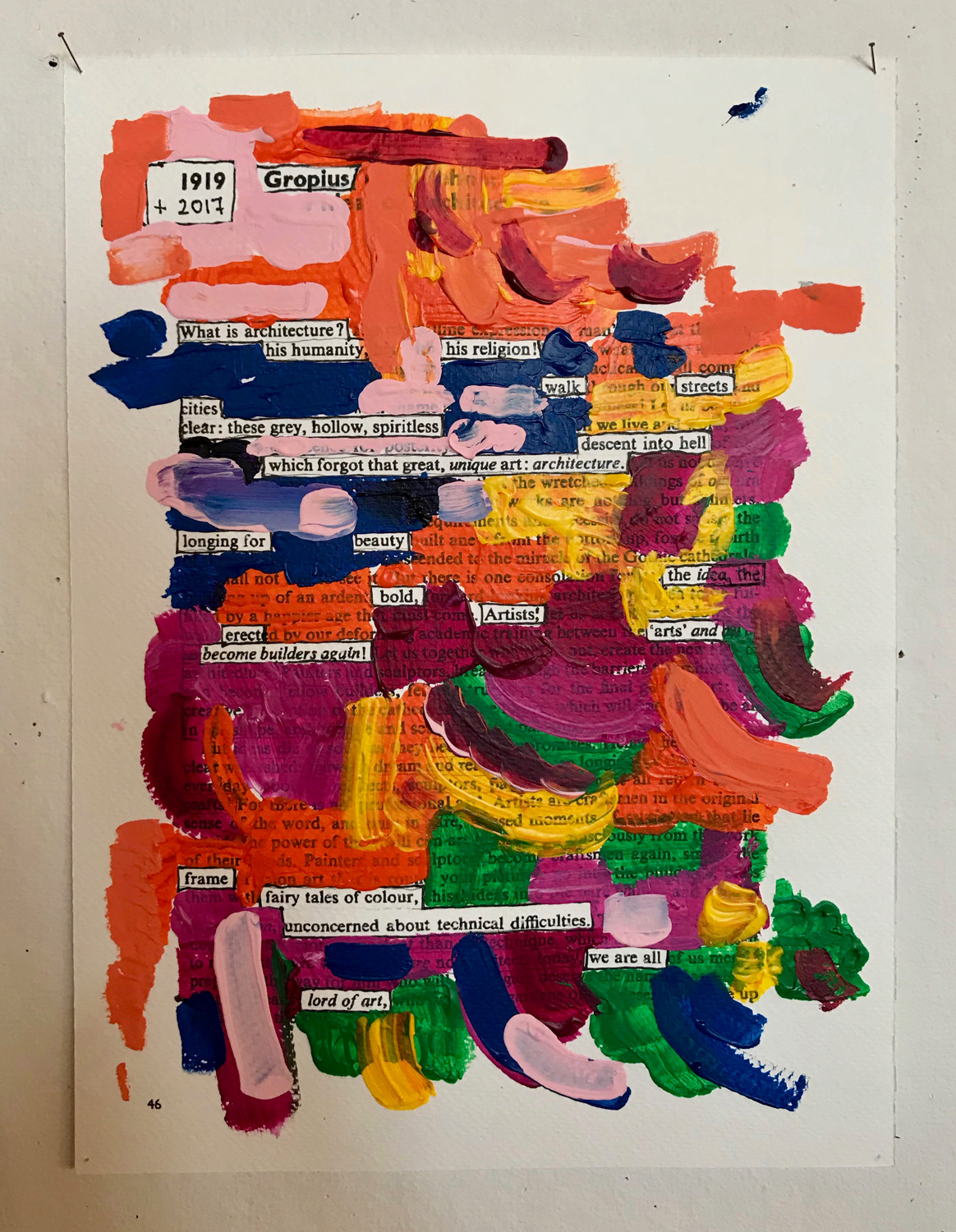

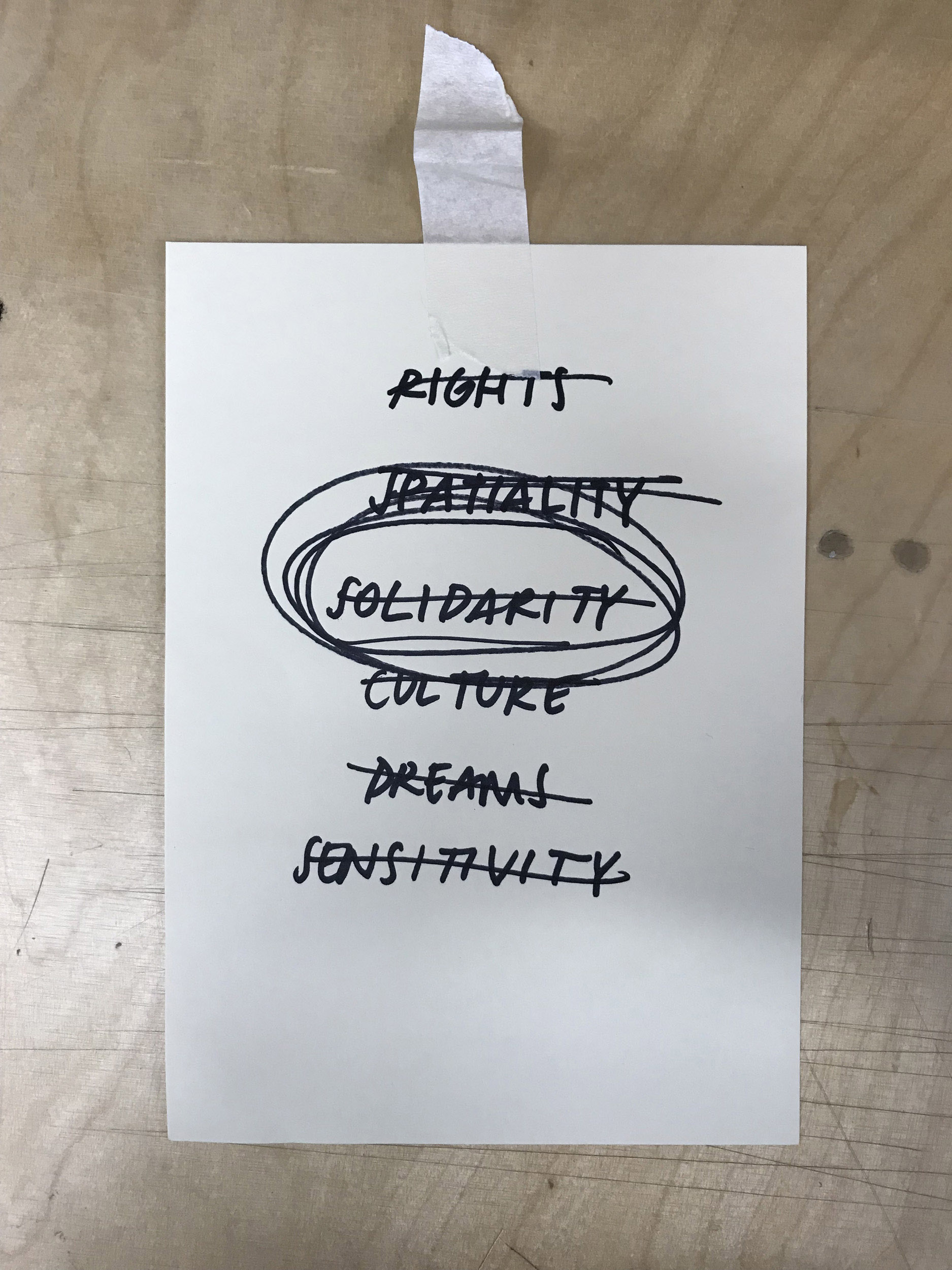

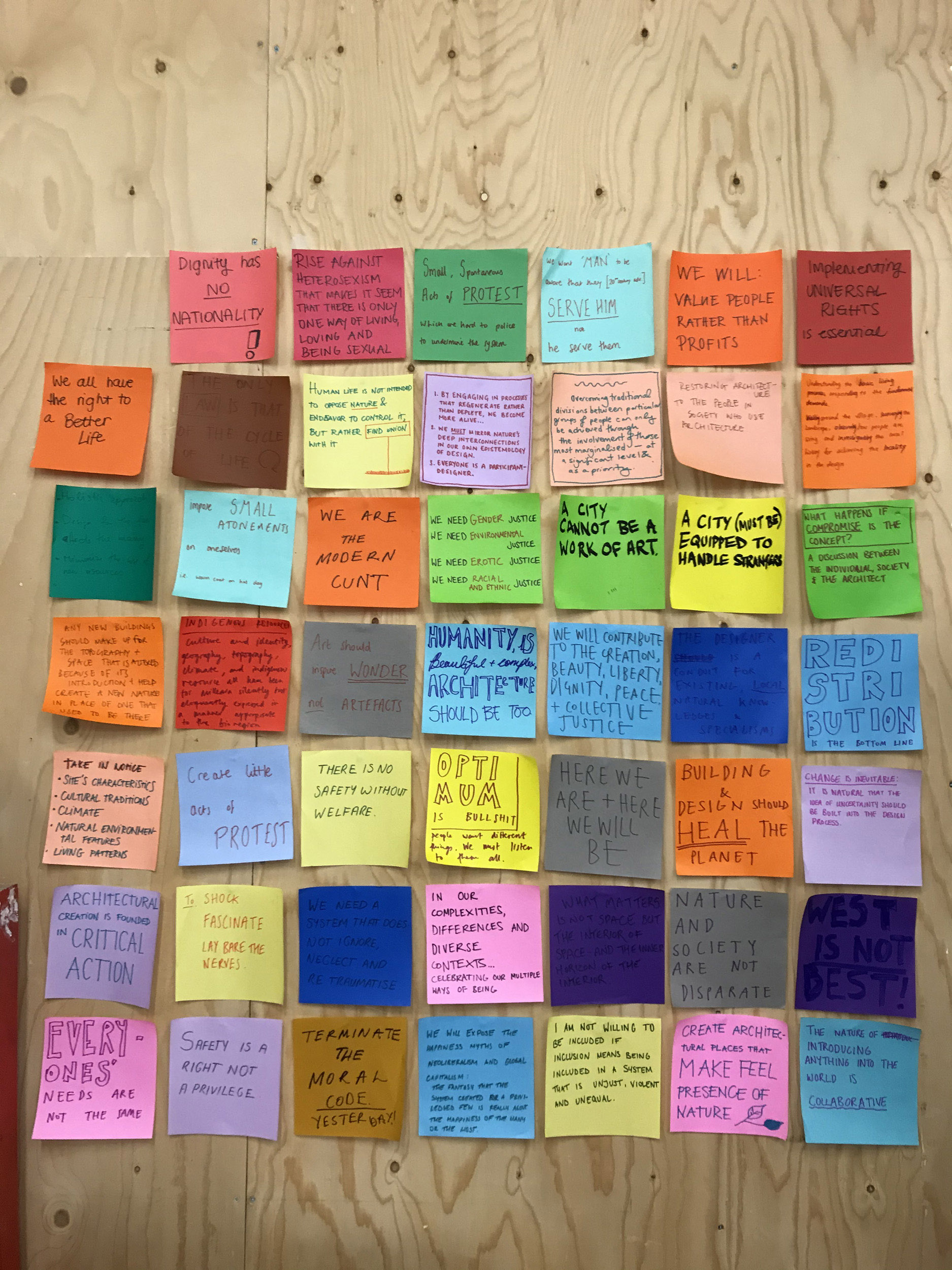

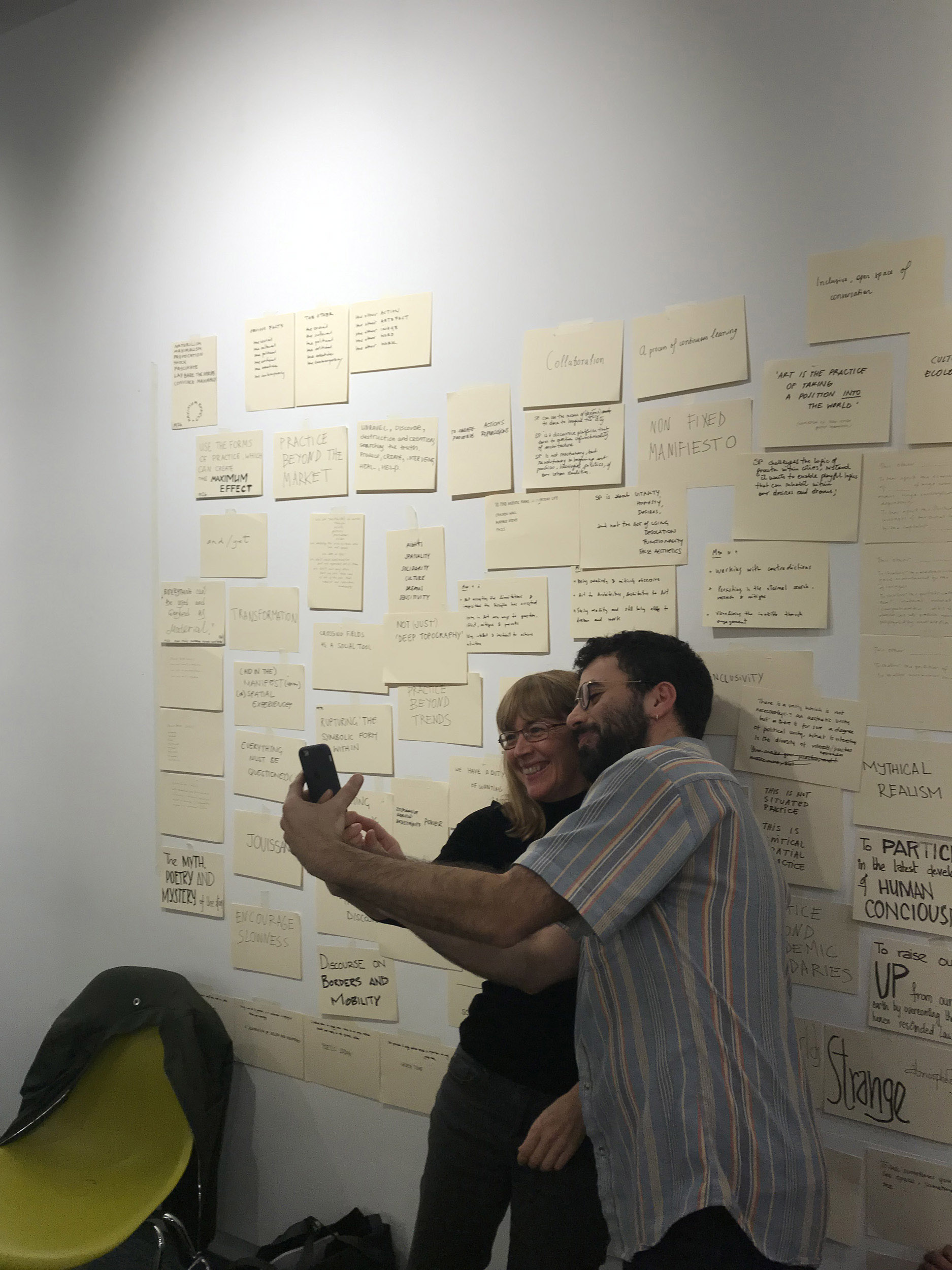

Drawing from new global anthologies from critic Jessica Lack and political scientist Penny Weiss, I invite each participant to read a selection of manifestos, to copy words, phrases and paragraphs that express their ethics onto multicoloured notes and affix them to a wall. As each person shares their rationale for including the line, careful to explain the author and context in which it was written, we listen to previously silenced stories in myriad political contexts, learn tactics to undermine colonialism and censorship, forge solidarity and collective identity (Weiss, 2018). The manifesto, Lack explains, 'opens up the space through which marginalised voices and experiences can attempt to make the voice of their diversity heard (Lack, 2017).

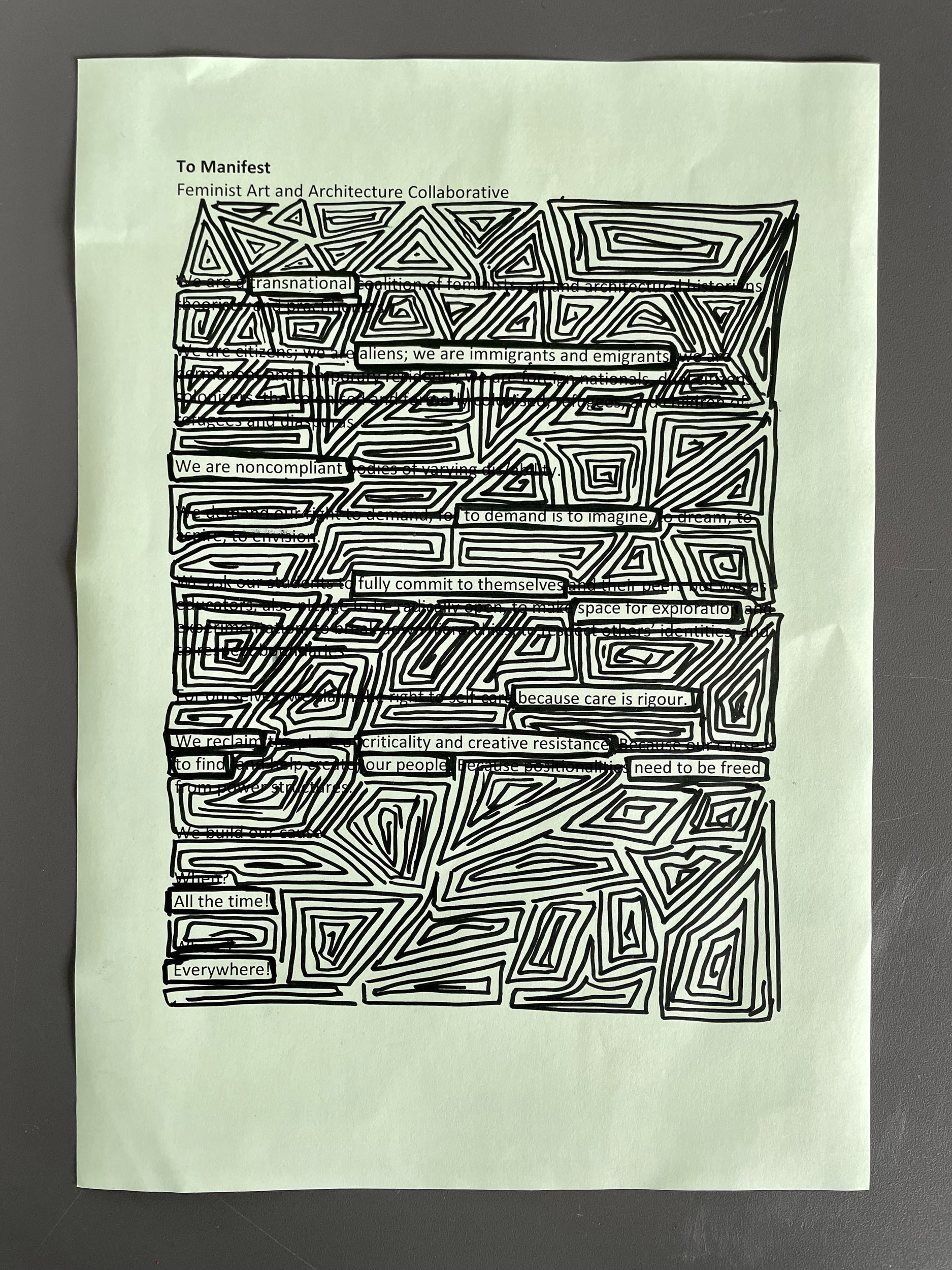

Taking inspiration from art collective Freee, we deliberate whether we agree with each word, phrase and point, considering which of these we wish to include or amend in our own response. The work of Freee art collective, comprising Dave Beech, Andy Hewitt, and Mel Jordan, uses manifestos, sculptural kiosks, spoken word choirs, and the ‘bodily endorsement of slogan’ in an attempt to form community forged in dialogue through the declaration of agreement and disagreement, seeking to reinvigorate manifesto writing as a practical tool for collective political engagement (Jordan, Beech & Hewitt, 2015). The act of drafting a manifesto involves both a relational act of working through as authors to respond to the principles and practices set out by others in relation to contemporary forces, and a reflexive relay of working towards that which not only reflects but projects as a directive for future acts (Caws, 2015). As we work through and towards, we move, reorder and rewrite notes across the wall and confront positionality which, as anthropologist Soyini Madison summarises, 'forces us to acknowledge our own power, privilege, and biases… When we turn back on ourselves, we examine our intentions, our methods, and our possible effects’ (Madison, 2005).

Rather than defining ourselves against other manifestos, or in reference to the canon, this approach encourages a manifesto defined with and through other writings, sayings and phrases from outside of what is conventionally regarded as architectural or urban practice. This inclusive gesture redefines both discipline and genre, reframing the manifesto from the individual to collective and opening the page as a collaborative site to an equal multiplicity of other voices.

We conclude by all reading lines together in a concerto of imagination and ideals. This process of collective deliberation and writing has an important history in feminism, as Weiss reminds 'collective authorship means that feminist manifestos not only inspire political action but also are the outcome of, or reflect feminist action – a diversity of voices, informed by experience and reflection and dialogue, together confronting enormous practical and theoretical problems.' (Weiss, 2008).

References

- Buckley, C. 2015. “After the Manifesto,” in Craig Buckley, ed. After the Manifesto: Writing, Architecture, and Media in a New Century. New York, NY: Columbia GSAPP Books on Architecture, 6–23.

- Caws, M. A. Mary. 2001. ed. Manifesto: a century of isms. London: University of Nebraska Press.

- Colomina, B. 2014. Manifesto Architecture: The Ghost of Mies. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Freee. 2012. The Manifesto for a New Public. Clapham Common Bandstand.

- Jordan, M., Beech, D. and Hewitt, A. 2015. To Hell with Herbert Read. Anarchist Studies, 23 (2), 38-46.

- Lack, J. 2017. ed. Why are we ‘Artists’? 100 World Art Manifestos. London: Penguin.

- Roberts, D. 2020. ‘Why Now?: The Ethics of Architectural Declaration’. Architecture and Culture.

- Soyini Madison. D. 2005. ‘Introduction to Critical Ethnography: Theory and Method,’ in Critical Ethnography: Method, Ethics, and Performance. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 14.

- Tayob, H. and Hall, S. 2019. Race, Space and Architecture: Towards an Open-access Curriculum, LSE.

- Weiss, P. 2018. ed. Feminist Manifestos: A Global Documentary Reader, New York, NY: New York University Press, 2.